Database

Challenges of Tracking Time in a Database

Tracking time sounds simple at first glance. A timestamp is just a date and a time, stored in a database field. Yet anyone who has worked with real-world systems quickly learns that time is one of the most complex and error-prone aspects of database design. Time zones, daylight saving changes, leap seconds, distributed users, and cloud-hosted infrastructure all introduce subtle issues that can lead to incorrect reports, broken workflows, and difficult-to-debug errors. As systems scale and users span multiple regions, these challenges multiply.

At the same time, many organizations have moved toward centralized, cloud-based systems that must handle time consistently across continents. While this approach has advantages, it also exposes every weakness in timestamp handling. In contrast, locally run software, operating within a single known time zone and under the direct control of the organization, can dramatically simplify time tracking and eliminate entire classes of problems. Understanding why this is the case requires a closer look at the nature of time in databases and the pitfalls that arise when time becomes global.

One of the fundamental challenges of timestamps is that time is contextual. A timestamp without context is ambiguous. The value "2026-01-01 09:00:00" means very different things depending on whether it refers to Eastern Time, Pacific Time, Coordinated Universal Time, or another zone entirely. Databases can store this value precisely, but they cannot inherently know what that time represents unless additional rules are enforced. Developers often assume a default timezone, either at the database server level or the application level, but those assumptions are easily broken when systems are moved, replicated, or accessed remotely.

Time zones themselves are a major source of complexity. There are dozens of active time zones, many of which do not align neatly with hourly offsets. Some regions observe daylight saving time, others do not, and the rules change over time based on government decisions. A database system must either store enough metadata to correctly interpret historical timestamps or risk misrepresenting past events. For example, an event logged at 2:30 a.m. on the day daylight saving time begins may never have actually occurred in local time, while an event logged during the "fall back" transition may occur twice. These edge cases can silently corrupt data or cause reports to show impossible sequences of events.

Distributed systems amplify these problems. In a cloud-hosted environment, the database server may be running in one timezone, application servers in another, and users accessing the system from many more. Best practice often dictates storing all timestamps in UTC and converting them to local time at the user interface level. While theoretically sound, this approach relies on perfect discipline across every layer of the system. One overlooked conversion, one misconfigured server, or one third-party integration that assumes local time can reintroduce errors. Over time, these inconsistencies accumulate, leading to databases filled with timestamps that are technically valid but semantically unreliable.

Another challenge is human expectation. Users think in local time. When someone enters "January 5th at 10 a.m." they are not thinking in UTC offsets or timezone conversions. They expect the system to behave as if time is absolute and intuitive. When a database stores time differently than users perceive it, confusion arises. Appointments appear to shift, logs seem out of order, and audit trails become difficult to interpret. Even when the underlying data is technically correct, the user experience suffers, and trust in the system erodes.

Reporting and historical analysis introduce further complications. When timestamps are converted dynamically based on current timezone rules, historical data may be reinterpreted incorrectly. A report generated today may show different times for events that occurred years ago if timezone rules have changed in the interim. This is particularly problematic for legal, financial, and compliance-related data, where accuracy and consistency over time are critical. The more layers of conversion applied to timestamps, the harder it becomes to guarantee that the reported time reflects what actually happened.

Against this backdrop, locally run software offers a compelling alternative for many use cases. When an application and its database run on a local machine or local network, operating within a single, known timezone, many of the above issues simply disappear. Time regains its intuitive meaning. A timestamp corresponds directly to the local clock on the system, and that clock is the same one users see on their wall or workstation. There is no need for constant conversion, offset calculations, or timezone metadata stored alongside every value.

Local software benefits from environmental consistency. The operating system, database engine, and application logic all share the same timezone configuration. This eliminates a common class of bugs where one component interprets time differently than another. When a record is created at 3:15 p.m., it is stored as 3:15 p.m. and retrieved as 3:15 p.m., with no hidden transformations. Debugging becomes easier because developers and administrators can reason about time directly, without mentally translating between zones.

Daylight saving time, while still present, becomes more manageable in a local context. Because the system operates entirely within a single locale, daylight saving transitions affect all timestamps uniformly. There is no need to reconcile data across regions that change clocks on different dates or not at all. While edge cases still exist, they are easier to understand and test because they align with local expectations. A business operating in one region typically already understands how daylight saving time affects its operations, and the software naturally follows those same rules.

Local software also simplifies auditing and compliance. When timestamps are stored in local time and never converted, audit logs reflect exactly what users experienced at the time of the event. This is especially valuable for small businesses, internal tools, and regulated environments where clarity is more important than global scalability. An auditor reviewing records does not need to ask what timezone the data was stored in or whether conversions were applied correctly. The timestamp speaks for itself.

Performance and reliability can also benefit. Timezone conversions are not computationally expensive individually, but they add complexity and processing overhead across large systems. Removing the need for these conversions simplifies code paths and reduces the risk of subtle bugs. More importantly, local systems are less dependent on external services or libraries for timezone data updates. In a cloud environment, outdated timezone definitions can lead to incorrect conversions until systems are patched. A local system, managed directly by its owner, can be updated on a controlled schedule with full awareness of its impact.

It is important to note that local software is not a universal solution. Global applications with users across multiple time zones must still confront the realities of distributed time. For such systems, UTC storage and careful conversion are unavoidable. However, many applications do not truly need global time awareness. Inventory systems, small business databases, personal data trackers, and internal tools often operate entirely within a single region. For these use cases, adopting cloud-style timestamp strategies introduces unnecessary complexity without meaningful benefit.

Running software locally also restores a sense of ownership and predictability. The database is not silently adjusting behavior based on a server located thousands of miles away. The clock that matters is the one the organization controls. This predictability makes long-term data more reliable. Records created years apart can be compared directly without worrying about how timezone policies or infrastructure changes may have altered their interpretation.

In practice, many of the most painful timestamp bugs arise not from time itself, but from mismatches between assumptions. One developer assumes local time, another assumes UTC, and the database quietly stores values without complaint. By constraining the system to a single timezone through local deployment, those assumptions are aligned by default. The system becomes harder to misuse accidentally, which is often more important than theoretical correctness.

In conclusion, tracking time and timestamps in databases is deceptively difficult. Time zones, daylight saving rules, distributed infrastructure, and human expectations all conspire to make time one of the most complex data types to handle correctly. While cloud-based and globally distributed systems must confront these challenges head-on, many applications can avoid them entirely by running locally. Local software, operating within a single, consistent timezone, simplifies timestamp storage, improves clarity, and reduces the risk of subtle and costly errors. For organizations whose needs are regional rather than global, this approach can turn time from a persistent problem into a dependable foundation.

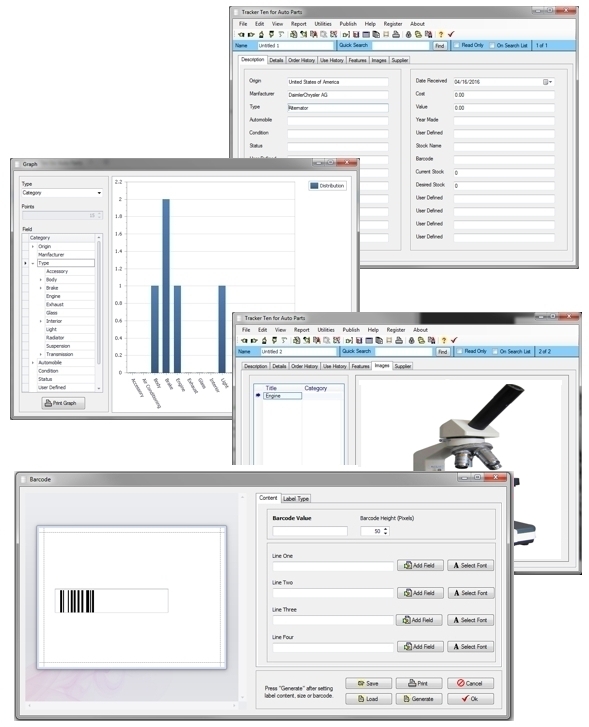

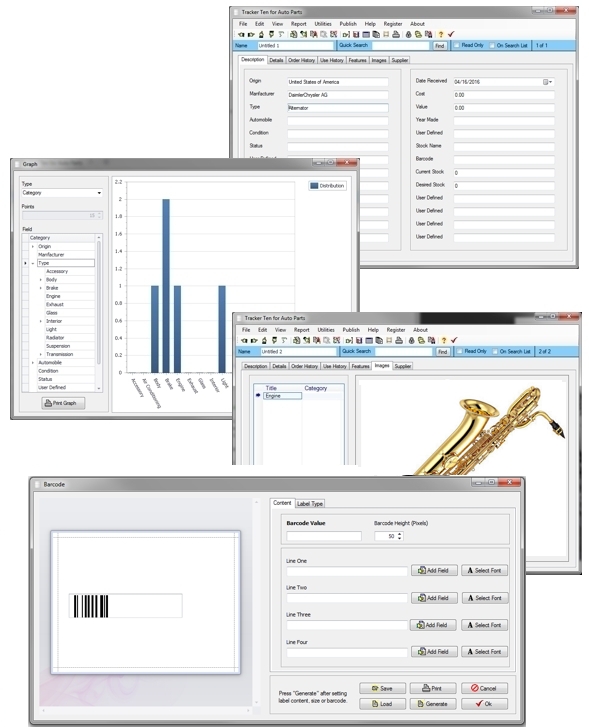

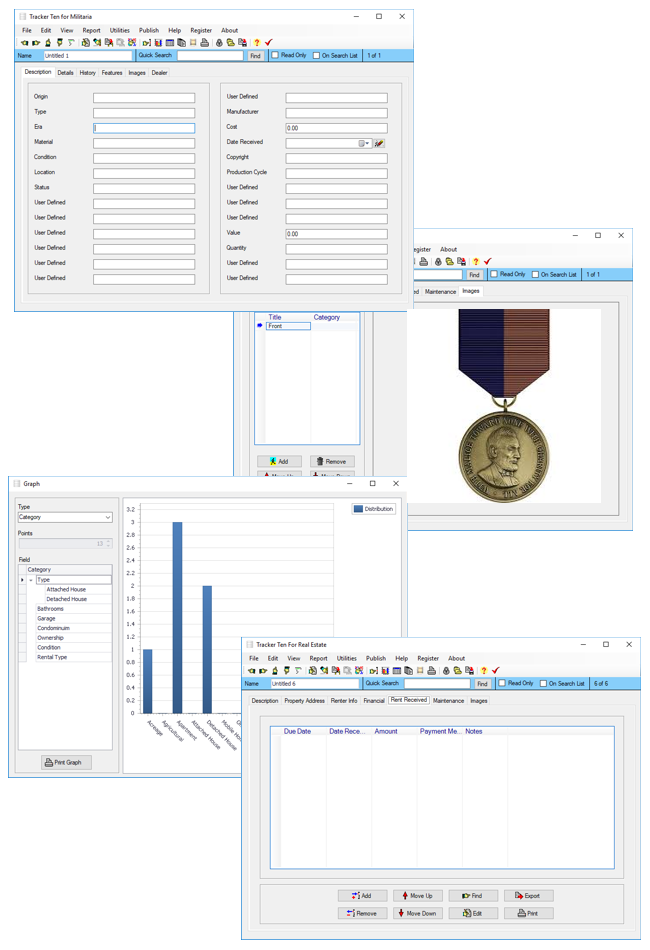

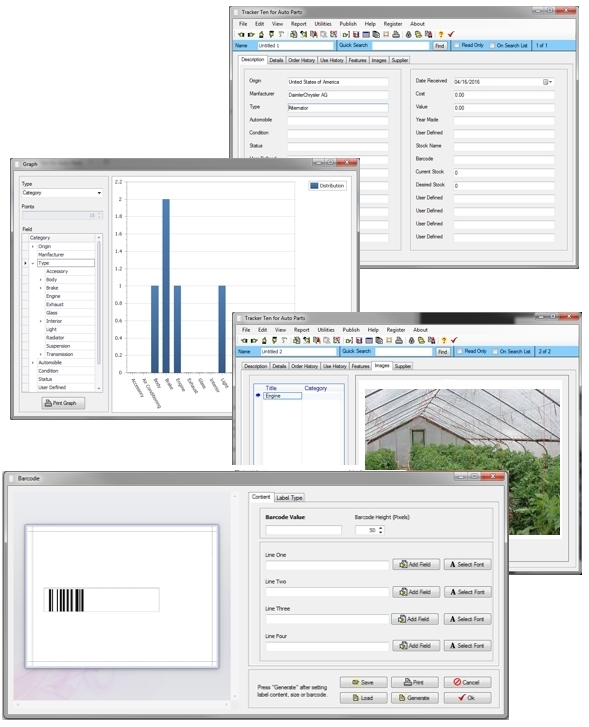

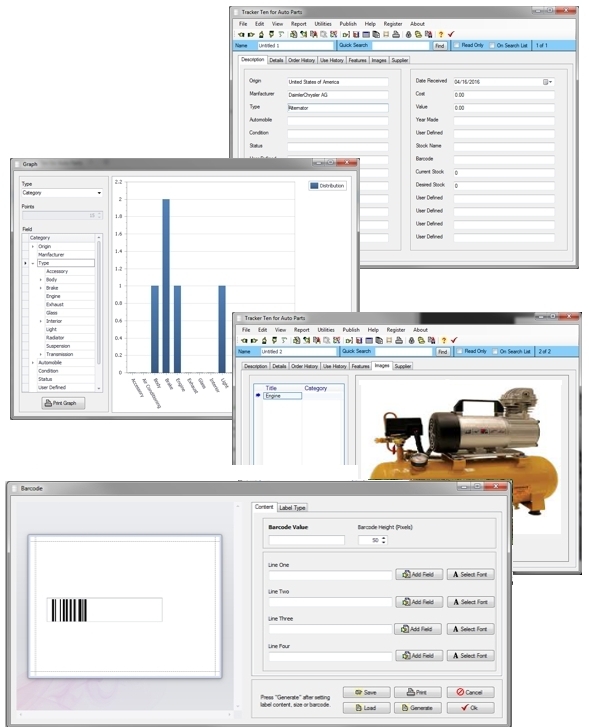

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Stamp Collecting Sunday, January 8, 2023

- NextChurch Member Tracking Wednesday, January 4, 2023