Database

Database Hardware Prerequisites

If you have decided that you need a database or a data warehouse, there are several important considerations to address before you even select and install a database management system. This is especially true if you plan to operate your own hardware and software rather than relying on a cloud-based service such as Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services, or a hosted shared or dedicated blade at a data center. While cloud platforms abstract much of the underlying infrastructure, on-premises or self-managed environments require careful planning to ensure reliability, performance, scalability, and long-term cost efficiency.

The focus of this article is to outline the many issues you need to consider when selecting, engineering, and configuring database hardware. When setting things up at your own site, you will not only need to purchase appropriate hardware, but you will also need to ensure that you have a stable electrical power supply, adequate cooling, sufficient physical space, and properly configured networking. These considerations often fall outside the traditional scope of database design, yet they play a decisive role in overall system performance and availability.

At this stage it is also important to understand the distinction between logical database requirements and physical database requirements. A logical database definition describes the tables needed to store your information, the relationships between those tables, indexing strategies, constraints, and user authorization rules, regardless of where the actual data is stored. A physical database definition, on the other hand, specifies the actual hardware, storage media, memory layout, and network architecture used to store and access the data. The physical database definition directly impacts hardware requirements, performance characteristics, and operational costs.

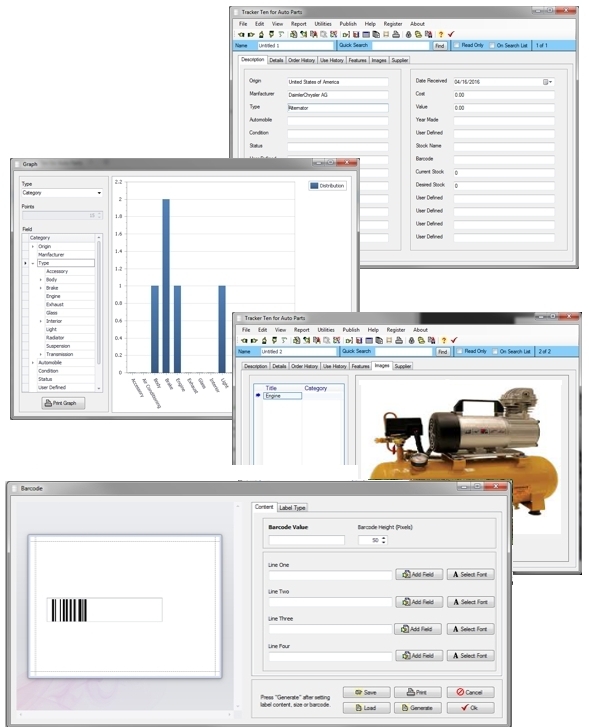

It does not matter whether you eventually choose a relational database system such as Microsoft SQL Server, PostgreSQL, MariaDB, MySQL, or Oracle, or a NoSQL solution such as MongoDB or Cassandra. Hardware awareness is equally important even if you select an off-the-shelf proprietary system like Tracker Ten or another specialized DBMS. Being rushed or overly frugal during the initial hardware selection stage often leads to future difficulties, including performance bottlenecks, frequent outages, and costly upgrades. While hardware pricing will always be a factor, it should never be the sole consideration. The ideal database hardware configuration varies by workload, but there are proven guidelines and best practices that can help you make informed decisions.

![]()

Selecting Database Hardware

Whether you are starting from scratch or building upon an existing system, you must ensure that your hardware configuration is capable of supporting the demands of a modern database system. Database workloads vary widely, but they are often memory-intensive and I/O-heavy. Extract, transform, and load (ETL) operations can consume large amounts of memory and disk bandwidth. Complex analytical queries may be CPU-intensive, while real-time dashboards and data visualization tools can place significant demands on graphics processing capabilities.

The scale of your data is another major factor. Databases that track millions or even billions of rows require hardware that can sustain consistent performance under heavy load. If your hardware becomes a bottleneck, even the most well-designed database schema and optimized queries will struggle to deliver acceptable response times. Ideally, your hardware should provide enough headroom to handle peak usage, future growth, and unexpected workloads.

Many of these challenges can be mitigated by selecting certified or vendor-recommended hardware. Some database systems are described as "close to the metal," meaning they are designed to take advantage of specific hardware features such as CPU instruction sets, memory hierarchies, and storage optimizations. Appliance layers like SAP HANA are engineered to maximize performance on Intel Xeon processors and benefit from advanced technologies such as NVMe storage and NVDIMM memory, which significantly reduce latency between storage and the CPU.

However, before investing in highly specialized hardware or advanced optimizations, it is critical to first determine the appropriate baseline configuration. Over-provisioning can be just as wasteful as under-provisioning, tying up capital in unused resources. The goal is to strike a balance between performance, scalability, reliability, and cost.

A solid understanding of your physical database requirements is essential. This includes estimating the amount of RAM needed, the volume and type of storage required, and the processing power necessary to support your workloads. You must also consider how many users will access the system concurrently, what types of queries they will run, and whether additional services such as reporting, analytics, or integration with external systems will be required. Without a strong hardware foundation, database performance will inevitably suffer.

Database Storage Requirements

When sizing your database and determining storage requirements, it is not enough to simply count the number of records. You must also consider the type of data being stored, the access patterns, and the expected rate of growth. Understanding the distinction between volatile memory (RAM) and persistent storage is fundamental. RAM is used for temporary data processing while the system is running, whereas persistent storage, such as hard drives or solid-state drives, retains data even when the system is powered off.

For a basic database system, a minimum of 4 GB of RAM is often recommended, keeping in mind that the operating system itself may consume 1 GB or more. Enterprise-level systems such as SQL Server or Oracle typically require significantly more memory, often starting at 16 GB and scaling upward depending on workload. As a general rule, you may want to allocate an additional 1 GB of RAM for every five concurrent users, though this varies widely depending on query complexity and application design.

It is also important to recognize that "users" may include more than just people logged in directly to the database. Web applications, APIs, automated processes, and background jobs all count as database consumers. For example, an e-commerce website may have hundreds of shoppers browsing inventory simultaneously, each generating database queries that consume resources.

When physical RAM is insufficient, the operating system may rely on virtual memory, using disk space to simulate additional RAM. While this prevents immediate system failure, it comes at a steep performance cost. Disk access is orders of magnitude slower than memory access, and excessive swapping can severely degrade database performance. In many cases, simply doubling the amount of physical RAM can dramatically improve response times and overall system stability.

Storage capacity requirements also depend heavily on data type. Textual data is relatively compact, while images, videos, and audio files consume significantly more space. In some cases, it may be more efficient to store large binary files in a dedicated file storage system and reference them from the database rather than storing them directly in database tables. Careful planning at this stage can prevent costly migrations later.

Application design plays a major role in determining future storage needs. Transactional systems that track sales, orders, or user activity may start small but grow rapidly over time. These systems typically require an OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) architecture optimized for frequent inserts and updates. In contrast, asset tracking or inventory systems may remain relatively stable in size but still require reliable performance and data integrity.

You should also consider concurrency and availability requirements. If a large number of users need simultaneous access, techniques such as replication, mirroring, or clustering may be necessary. These approaches increase hardware requirements but provide improved fault tolerance and scalability. Backup systems and failover mechanisms further add to storage and infrastructure needs, yet they are essential for protecting against data loss and minimizing downtime.

In addition to capacity, storage technology choices have a profound impact on performance. Traditional magnetic hard drives are cost-effective but relatively slow. Solid-state drives (SSDs) offer much faster access times but come at a higher cost per gigabyte. NVMe storage provides even lower latency and higher throughput, making it ideal for high-performance database workloads. RAID configurations, network-attached storage (NAS), and data striping techniques can further enhance performance and resilience when properly configured.

Don’t Forget About Database Backups

When calculating storage requirements, it is easy to overlook the space needed for backups. Regular backups are essential for disaster recovery, compliance, and long-term data retention. Depending on your backup strategy, you may need storage equal to several full copies of your database, along with incremental or differential backups. For more detailed guidance, see our articles on Making a Full Database Backup and When to Archive Data.

Database Processor Requirements

Processing power is another critical component of database hardware. Modern databases can take advantage of multiple CPU cores to execute queries in parallel, handle concurrent connections, and perform background maintenance tasks. All major chip manufacturers, including Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA, offer processors suitable for database workloads.

For a basic single-user or small workgroup database, a dual-core processor may be sufficient. As workloads grow in complexity and concurrency, additional cores become increasingly important. Enterprise systems often utilize processors with 8, 16, or more cores, sometimes across multiple CPU sockets on a single motherboard. Multi-socket systems allow for significant scalability but also require careful consideration of memory architecture and interconnect performance.

Clock speed, cache size, and instruction set support also influence database performance. Some workloads benefit from higher clock speeds, while others scale more effectively with additional cores. Understanding your specific workload characteristics can help you choose the most appropriate processor configuration.

Hardware Electrical Power Requirements

In many environments, databases are expected to be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This requires more than just plugging hardware into a standard power outlet. Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), backup generators, and surge protection systems are essential components of a reliable database infrastructure.

Power interruptions can lead to data corruption, hardware damage, and extended downtime. A properly sized UPS can provide enough power to allow for graceful shutdowns or short-term continued operation during outages. For mission-critical systems, generators may be necessary to sustain operations during prolonged power failures. It is also important to ensure that power systems are capable of supporting the full load of your database hardware, including servers, storage devices, and networking equipment.

Database Networking Requirements

Multi-user databases require reliable network connectivity. Networking hardware may include network interface cards, switches, routers, firewalls, and cabling. While wireless connections offer convenience, they are generally not recommended for database servers due to their susceptibility to interference and dropped connections.

A wired Ethernet connection with a fixed IP address provides greater stability and predictability. Proper network configuration ensures that clients can consistently communicate with the database server and that latency is minimized. Network bandwidth becomes especially important for distributed systems, replication, and remote access scenarios.

It is also important to distinguish between multi-user database systems and distributed database architectures. In a traditional multi-user system, all clients connect to a central database server that handles all processing. In a distributed architecture, processing may be spread across multiple servers, often using multi-tier designs with load balancers and service layers. Distributed systems can offer improved scalability and resilience but require more complex networking and hardware planning.

Database GPU Requirements

While not all database systems require a graphics processing unit, GPUs can play an important role in data visualization, analytics, and certain types of parallel computation. If your workload involves rendering complex charts, dashboards, or three-dimensional visualizations, a dedicated GPU can significantly improve performance and user experience.

Integrated graphics solutions are often insufficient for demanding visualization tasks. Dedicated GPUs from manufacturers such as NVIDIA and AMD provide specialized hardware for rendering and parallel processing. In some cases, GPUs can also accelerate data analysis and machine learning workloads, acting as additional computational resources alongside the CPU.

When selecting a GPU, ensure compatibility with your visualization tools and drivers. Consider scalability as well, as future requirements may necessitate more powerful or additional GPUs.

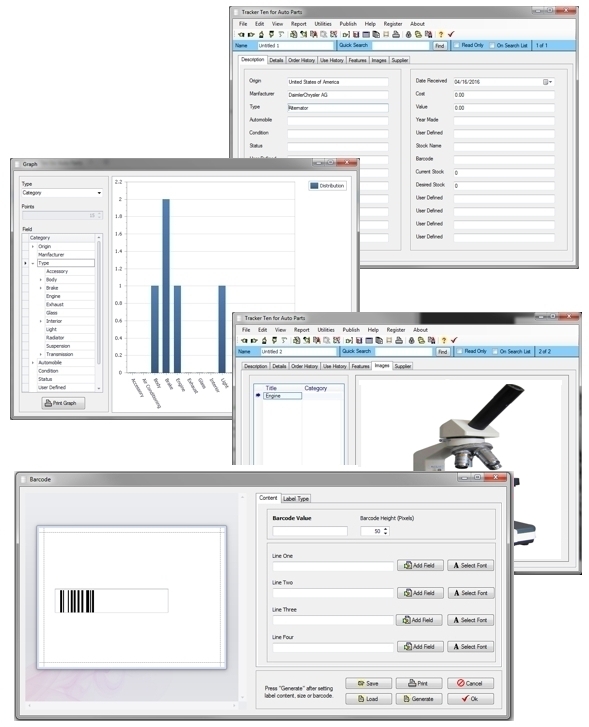

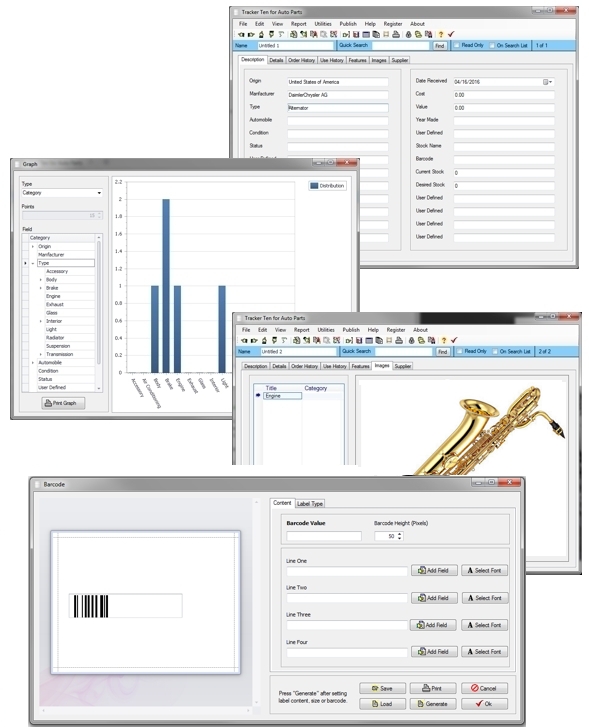

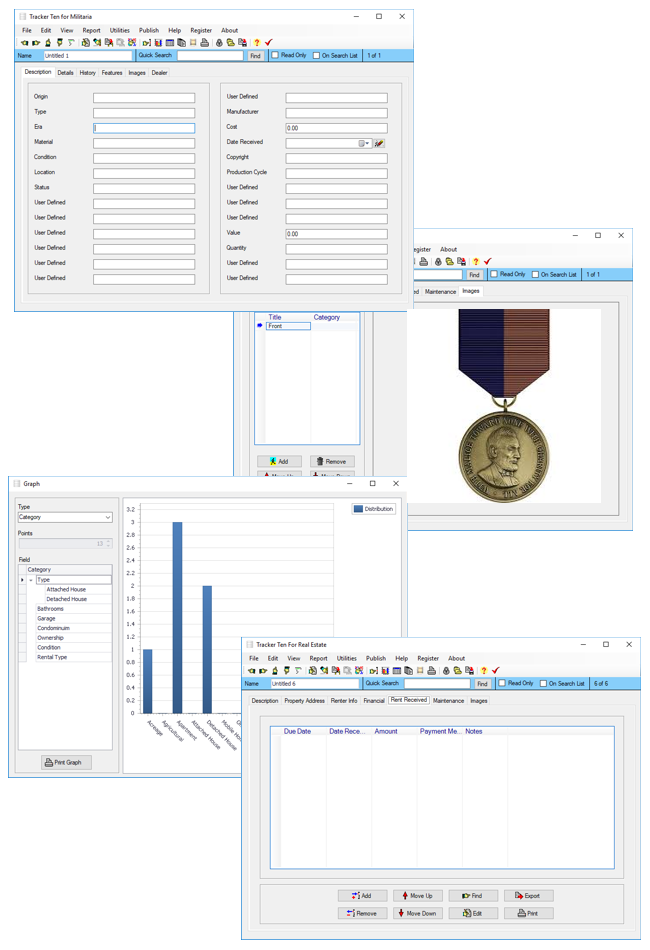

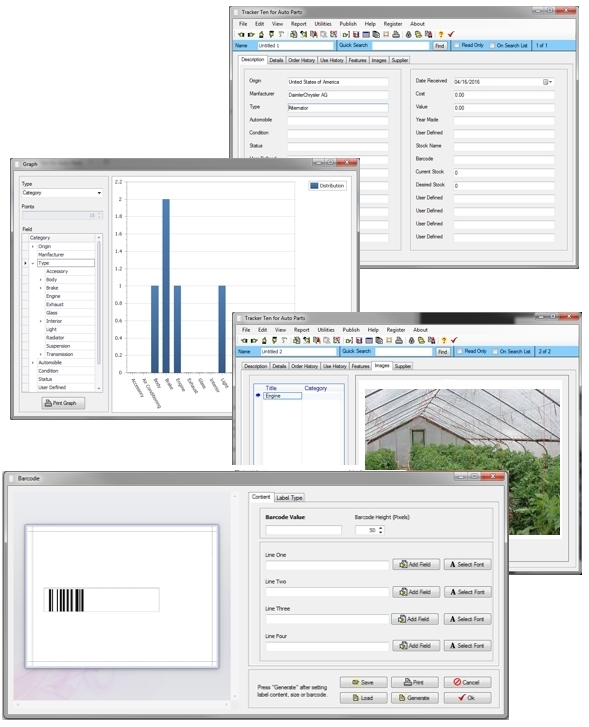

Tracker Ten

Our own Tracker Ten database system runs on Microsoft Windows computers and is designed to scale across a wide range of hardware configurations. By applying the guidelines outlined in this article, you should be able to determine the appropriate hardware size and features required to run Tracker Ten smoothly based on your specific needs. Thoughtful planning at the hardware level ensures long-term reliability, performance, and return on investment.

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Keeping Track of Cattle for your Ranch or Farm Monday, October 9, 2023

- NextCollecting War Medals Wednesday, September 20, 2023