Database

Database Searching Techniques

Effectively finding information in a large digital database is both an art and a science. Once you have loaded a database with valuable information, that data only becomes useful if you can retrieve it quickly and accurately when needed. A well-designed database can still feel overwhelming if users do not understand how to search it properly. Fortunately, database searching is not an exotic or highly technical skill reserved for specialists. It is something most people already practice every day, often without realizing it.

If you discovered this article through a search engine such as Google, Bing, or DuckDuckGo, you already performed a database search. Search engines are essentially massive databases that index billions of records and return the most relevant results based on your query. Similarly, when you browse an online store, search your email inbox, or look for a contact in your phone, you are interacting with a database search system.

Even everyday offline activities closely resemble database searching. Consider a trip to the grocery store. If you need bananas, you instinctively narrow your search to the produce section, then visually scan until you find the correct bin. You do not search every aisle randomly. You apply filters—location, category, and visual recognition—to retrieve exactly what you need. Database searching works in the same way. You must search the correct part of the database and apply the right criteria to retrieve the records that matter.

Database searching becomes increasingly important as databases grow larger and more complex. A small personal database with a few dozen records might be easy to browse manually, but enterprise systems can contain millions or even billions of records. Without effective search techniques, valuable information becomes effectively lost, buried beneath irrelevant results.

It is also important to understand that search proficiency develops over time. Your first search attempt may not return the results you expect, and that is perfectly normal. Searching is an iterative process. You refine your terms, adjust filters, and try different strategies until you reach the desired outcome. With practice, database searching becomes intuitive and efficient.

![]()

Understanding How Databases Store Information

Before exploring specific search techniques, it helps to understand how databases store information. Most databases organize data into records and fields. A record represents a single entity, such as a customer, product, document, or event. Fields represent attributes of that entity, such as name, date, category, price, or description.

When you search a database, you are typically searching one or more fields across multiple records. Some searches examine every field, while others are limited to specific columns. Knowing which fields contain the most relevant information allows you to target your searches more effectively.

Databases may also index certain fields to speed up searching. An index is a data structure that allows the database to locate records quickly without scanning every entry. Fields such as names, IDs, dates, and keywords are often indexed. Understanding which fields are indexed can help explain why some searches are fast and others are slow.

Additionally, databases may support different data types, including text, numbers, dates, geographic coordinates, images, and binary data. Each data type may support different search operations, such as numeric ranges, date comparisons, or spatial proximity.

Database Search Boolean Operators

Boolean operators form the foundation of most database search systems. They define relationships between words or phrases in a search query and determine how results are matched. The three most common Boolean operators are AND, OR, and NOT.

- AND – Results must contain all terms connected by the AND operator. For example, a search for database AND security returns records that include both words. In many search engines and databases, AND is implied. Searching for database security often produces the same result.

- OR – Results may contain any of the terms connected by the OR operator. A search for database OR spreadsheet returns records containing either term, or both.

- NOT – Results must exclude the term following the NOT operator. Searching for database NOT cloud returns records that mention databases but exclude cloud-related content. Some systems allow the minus sign (-) as a shorthand for NOT.

Boolean operators can be combined to create more advanced search expressions. For example, (database AND security) OR encryption returns records that either contain both "database" and "security" or contain "encryption." Operator precedence matters: AND operations are usually evaluated before OR unless parentheses are used.

Quotation marks can be used to search for exact phrases. A search for "data integrity" returns records where those words appear together in that exact order. Parentheses allow you to group terms and control the order in which expressions are evaluated.

Keyword Searches Versus Subject Searches

Keyword searching is the most common form of database search. It looks for records that contain the specified words anywhere within selected fields. While keyword searches are flexible and easy to use, they can return a large number of irrelevant results if the terms are too broad.

Subject searching offers a more controlled approach. In subject searches, records are tagged with standardized subject headings or categories. When you search by subject, only records explicitly associated with that subject are returned. This can significantly improve relevance but may exclude useful records that were not tagged correctly.

Academic databases, library catalogs, and enterprise content management systems often support subject searching. Understanding the subject taxonomy used by a system can dramatically improve search precision.

Truncation and Wildcard Searches

Truncation and wildcard searching allow you to account for variations in spelling, word endings, and terminology. A wildcard represents one or more characters within a word. The most common wildcard symbol is the asterisk (*), though some systems use question marks or percent signs.

For example, searching for comput* may return results containing "computer," "computing," "computation," and "computational." This technique is especially useful when you are unsure of the exact wording used in the database.

Wildcards can also be used to handle spelling differences between regions, such as colo*r to match both "color" and "colour." However, excessive use of wildcards can reduce search performance and return too many irrelevant results.

Advanced Filtering and Faceted Search

Many modern databases provide filtering tools that allow users to narrow results without modifying the search query itself. Filters may include date ranges, categories, locations, numeric thresholds, or status flags.

Faceted search is a powerful extension of filtering. It allows users to dynamically refine results by selecting values from multiple facets, such as author, topic, file type, or year. Each selection updates the result set in real time.

Faceted search is common in e-commerce, document management systems, and digital libraries because it provides an intuitive way to explore large datasets without requiring complex queries.

Database Search Pitfalls

Several common issues can reduce search effectiveness. One of the most frequent problems is spelling errors. If either the stored data or the search query contains mistakes, matching records may not be found. Implementing validation and spell-checking during data entry can significantly improve search reliability.

International spelling variations can also cause missed results. Words like "labor" and "labour," or "organization" and "organisation," may require multiple search variants. Wildcards or OR operators can help address this issue.

Overly specific searches may return no results at all. When this happens, broadening the search terms or removing less critical conditions can help. Conversely, searches that are too broad may return an overwhelming number of results, requiring additional refinement.

Synonyms present another challenge. Different users may describe the same concept using different words. Consulting a thesaurus or controlled vocabulary can help identify alternative terms.

What Happens When You Get Too Many Results?

Receiving too many results can be just as frustrating as receiving none. This usually indicates that the search terms are too general. Adding additional keywords, using exact phrases, or applying filters can significantly reduce result volume.

For example, searching for "car" may return millions of records. Refining the search to "electric car," "Tesla," or "electric vehicle battery" dramatically improves relevance.

Sorting results by relevance, date, or popularity can also help surface the most useful records first.

Geographic Proximity Searches

Geographic proximity searching allows users to find records based on physical distance. These searches are common in mapping applications, real estate databases, delivery services, and location-based marketing platforms.

To support proximity searches, databases must convert addresses into geographic coordinates using geocoding. Distances are then calculated using mathematical formulas such as the Haversine formula.

Proximity searches enable queries like "restaurants within five kilometers" or "warehouses near Toronto." These searches are especially valuable in logistics, emergency response, and urban planning.

Database Searching in Bioinformatics

Some fields require highly specialized search techniques. In bioinformatics, databases store genetic sequences, protein structures, and molecular data. Searches may involve matching nucleotide patterns, amino acid sequences, or structural motifs.

These searches rely on specialized algorithms such as BLAST and require significant computational resources. Results are often ranked by similarity scores rather than exact matches.

Organizations with unique or complex search requirements may require custom-built solutions to support specialized data structures and query logic.

Voice Assistants and Natural Language Search

![]()

Voice-controlled assistants such as Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, and Apple Siri have transformed how users interact with databases. These systems use natural language processing to convert spoken queries into structured database searches.

Rather than typing precise keywords, users ask questions in conversational language. The system interprets intent, identifies relevant entities, and retrieves the most appropriate results.

As natural language technology improves, database searching is becoming more accessible to non-technical users. Voice and conversational interfaces reduce the learning curve and enable hands-free interaction.

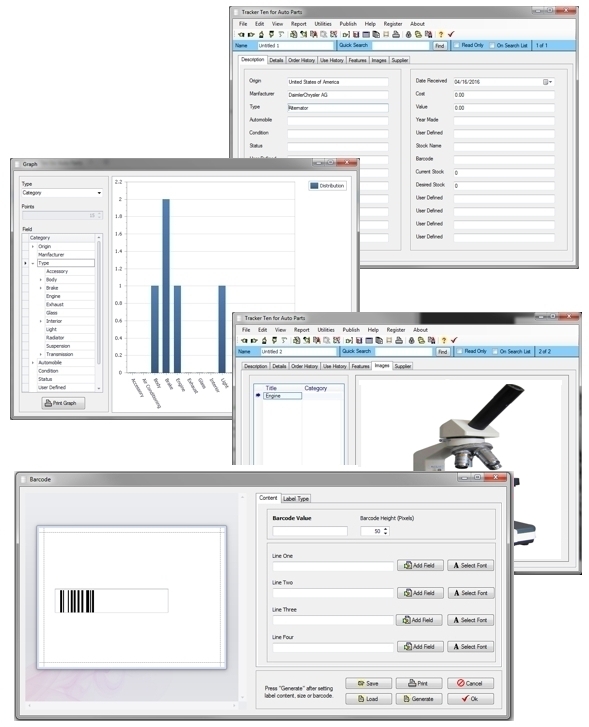

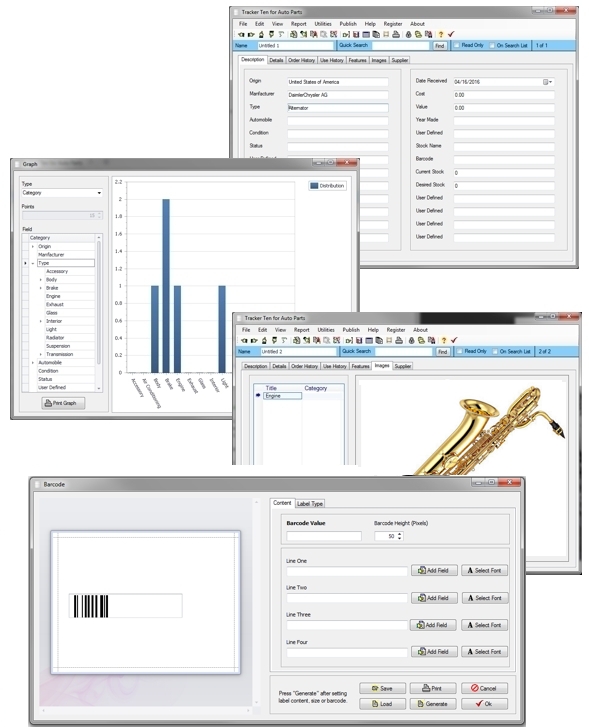

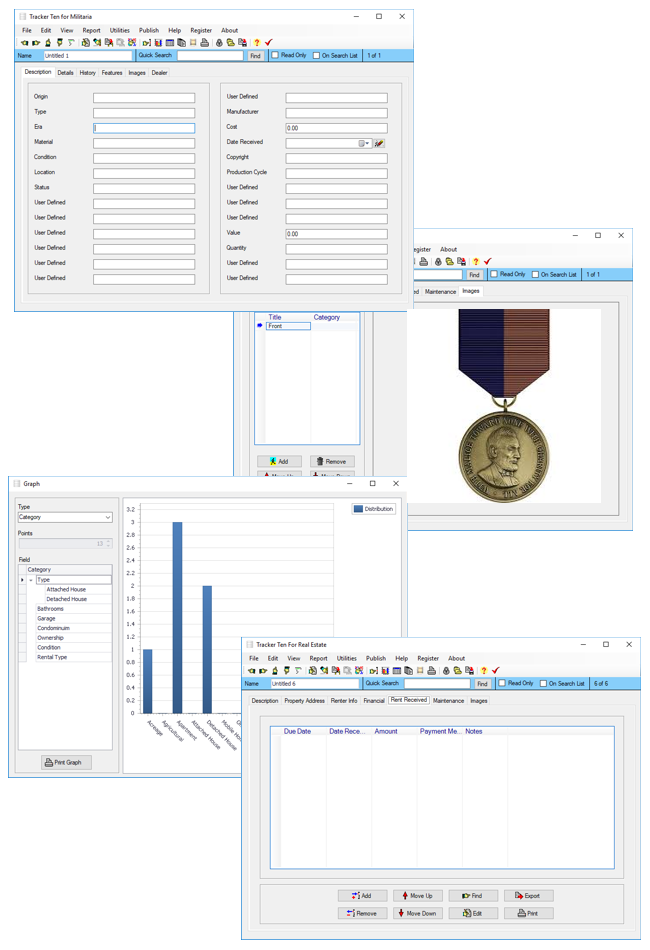

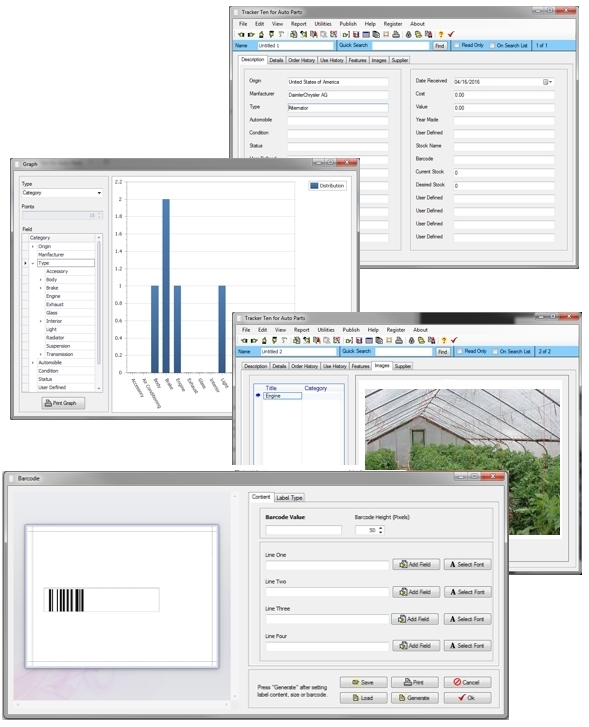

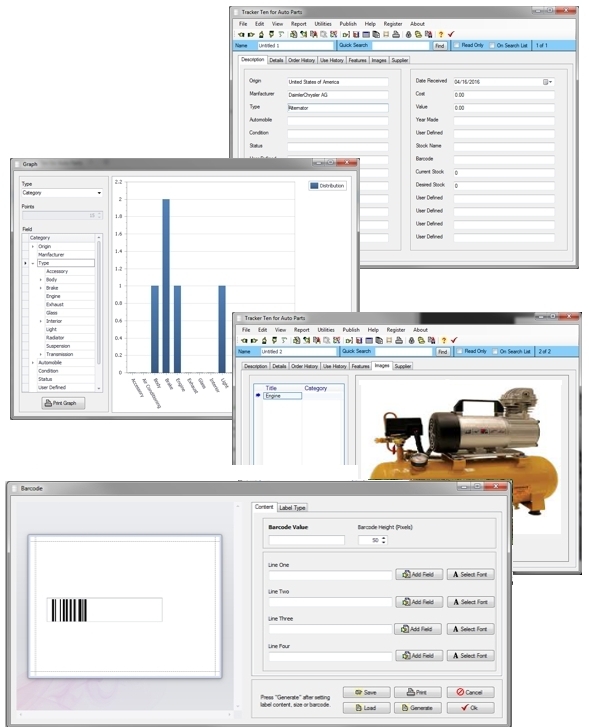

Tracker Ten Searches

Our Tracker Ten database system is designed to make searching intuitive and efficient. It provides a visual interface that allows users to build complex Boolean queries without writing code.

Users can combine multiple search conditions, apply filters, and preview results instantly. Searches can be saved and reused, making it easy to run recurring reports or locate frequently accessed records.

By simplifying advanced search techniques, Tracker Ten empowers users to fully leverage their data, turning stored information into actionable knowledge.

In conclusion, effective database searching is a critical skill in the digital age. By understanding how databases store information and applying proven search techniques, users can retrieve relevant data quickly and confidently. With practice and the right tools, even the largest databases become manageable and valuable resources.

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Downloading Software Tuesday, March 26, 2024

- NextMedical Equipment Inventory Saturday, March 16, 2024