Database

Storing Geographic Information in a Database

Storing geographic information in a database is a foundational requirement for many modern applications, ranging from mapping and navigation systems to logistics platforms, urban planning tools, environmental monitoring, and location-based services. Geographic information, often referred to as spatial or geospatial data, represents real-world locations, shapes, and spatial relationships. Effectively storing this type of data requires an understanding of both traditional database principles and the unique characteristics of geographic information.

At its simplest level, geographic data represents "where" something is. This can be as basic as a latitude and longitude pair identifying a single point on the Earth’s surface, or as complex as multi-layered polygon datasets describing country borders, land parcels, road networks, or climate zones. Unlike typical numeric or textual data, geographic data has spatial meaning. Two values that appear close numerically may be far apart geographically, and spatial relationships such as distance, containment, and intersection are often more important than exact values.

One of the earliest and most straightforward ways to store geographic information in a database is by using plain numeric fields for latitude and longitude. In this approach, each record contains two floating-point values representing coordinates, usually in the WGS84 coordinate system. This method is simple, widely supported, and easy to understand. It works well for basic use cases such as storing the location of customers, stores, or points of interest. Applications can retrieve these values and perform simple calculations or pass them to mapping libraries for visualization.

However, storing coordinates as plain numbers has limitations. While it allows basic location storage, it does not inherently support spatial queries such as finding all points within a certain distance, determining whether a point lies within a region, or calculating accurate distances over the Earth’s curved surface. These operations require additional logic at the application level, which can become complex and inefficient as data volumes grow.

To address these challenges, many databases support specialized spatial data types. These data types are designed specifically to represent geographic shapes such as points, lines, and polygons. A point might represent a single location, a line could represent a road or river, and a polygon might represent a city boundary or land parcel. By storing geographic information in these native spatial formats, databases can understand the geometry of the data and perform spatial operations directly.

Relational databases such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQL Server offer spatial extensions or built-in support for geographic data. These systems allow developers to store geometry or geography columns alongside traditional fields. The geometry type typically represents data in a flat, planar coordinate system, while the geography type accounts for the Earth’s curvature, enabling more accurate distance and area calculations over large regions. Choosing between these types depends on the scale and accuracy requirements of the application.

Spatial indexing is another critical aspect of storing geographic information effectively. Traditional database indexes are designed for linear data, such as numbers or strings. Geographic data, however, exists in multiple dimensions. Spatial indexes, such as R-trees or quad-trees, are designed to index shapes and locations efficiently. They allow the database to quickly narrow down candidate records when performing spatial queries, such as finding all features within a bounding box or radius. Without spatial indexing, queries on large geographic datasets can become prohibitively slow.

Beyond relational databases, NoSQL and specialized spatial databases also play an important role in geographic data storage. Document databases can store geographic information as structured objects, often following formats like GeoJSON. GeoJSON represents geographic features using JSON, making it easy to store, transmit, and integrate with web applications. Many modern databases and APIs understand GeoJSON directly, allowing seamless integration between storage and visualization layers.

Search-oriented databases and engines often include geospatial capabilities as well. These systems are optimized for fast retrieval and filtering and can store geographic points and shapes with built-in support for distance queries and bounding boxes. This makes them well suited for applications such as real-time search, ride-sharing platforms, and location-based recommendations, where speed and scalability are critical.

Another important consideration when storing geographic information is coordinate reference systems. Geographic data can be expressed in many different coordinate systems and projections. Latitude and longitude are common, but they are not always ideal for all applications. Some projections preserve distance, others preserve area, and others preserve shape. Mixing data from different sources without understanding their coordinate systems can lead to errors and inconsistencies. A well-designed database schema should standardize on a specific coordinate system or clearly document and manage transformations between systems.

Data accuracy and precision are also central concerns. Geographic information often comes from diverse sources, such as GPS devices, satellite imagery, user input, or legacy datasets. Each source has its own level of accuracy and potential error. Storing metadata about data sources, collection methods, and timestamps can be just as important as storing the coordinates themselves. This contextual information helps users and applications interpret the data correctly and assess its reliability.

Temporal aspects further complicate geographic data storage. Many geographic features change over time. Roads are built or rerouted, boundaries are redrawn, and environmental conditions evolve. In some applications, it is important not only to know the current state of a geographic feature but also its history. Supporting temporal versioning in a database allows systems to track changes over time, enabling historical analysis and audits. This can be achieved through techniques such as timestamped records, version tables, or temporal database features.

Scalability is another key factor. Geographic datasets can become very large, especially when dealing with high-resolution maps, sensor data, or global coverage. Efficient storage strategies, indexing, and partitioning become essential. Some systems partition data geographically, dividing the world into regions or tiles and storing each segment separately. This approach can improve performance and manageability, particularly in distributed database environments.

Security and privacy considerations also apply when storing geographic information. Location data can be highly sensitive, revealing patterns about individuals, businesses, or critical infrastructure. Databases storing geographic information must implement appropriate access controls, encryption, and data retention policies. In some cases, it may be necessary to anonymize or generalize location data to protect privacy while still supporting analysis.

Interoperability is another important dimension. Geographic data is often shared between systems, organizations, and applications. Adhering to widely accepted standards for data formats and representations helps ensure compatibility. Standards such as GeoJSON, Well-Known Text, and Well-Known Binary provide common ways to encode geographic information. Using standard formats makes it easier to integrate with mapping libraries, GIS software, and external data providers.

Performance considerations extend beyond query speed. Storing geographic data efficiently also affects storage size and maintenance overhead. High-precision coordinates and complex geometries can consume significant space. Techniques such as geometry simplification, tiling, or multi-resolution storage can help balance accuracy and performance. For example, an application might store simplified shapes for overview maps and detailed shapes for zoomed-in views.

The choice of database technology ultimately depends on the specific requirements of the application. Simple applications may only need to store a few coordinates and perform basic lookups. More advanced systems may require full spatial analysis, complex geometry operations, and high scalability. Understanding the trade-offs between simplicity, performance, accuracy, and complexity is essential when designing a database for geographic information.

In practice, storing geographic information in a database is not just about choosing the right data type. It involves thoughtful schema design, indexing strategies, data governance, and an awareness of how the data will be queried and used. When done correctly, a well-designed geographic database becomes a powerful foundation for location-aware applications, enabling insights and capabilities that would be difficult or impossible with non-spatial data alone.

As location-based technologies continue to grow in importance, the ability to store and manage geographic information effectively will remain a critical skill. From everyday applications like maps and delivery tracking to advanced fields like environmental science and urban planning, geographic databases play a central role in connecting digital systems to the physical world.

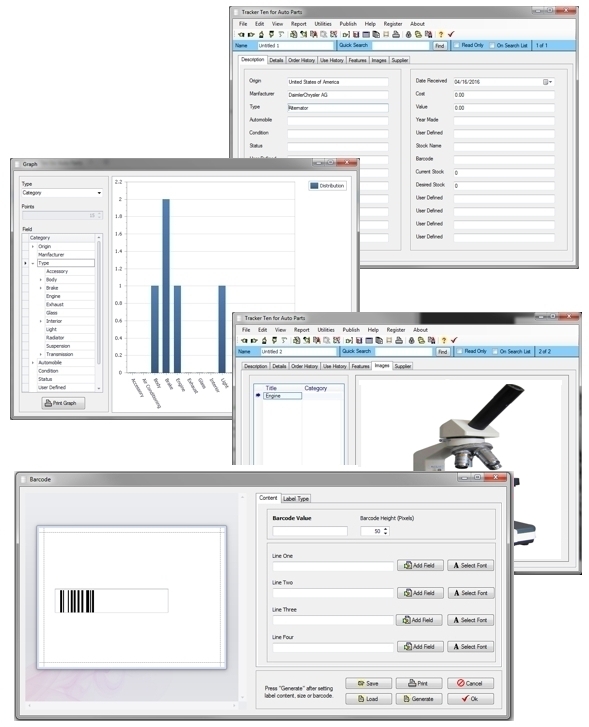

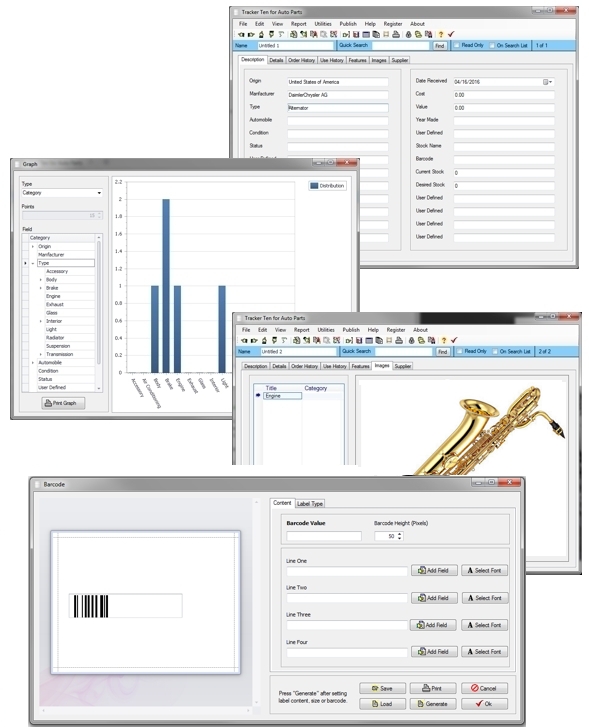

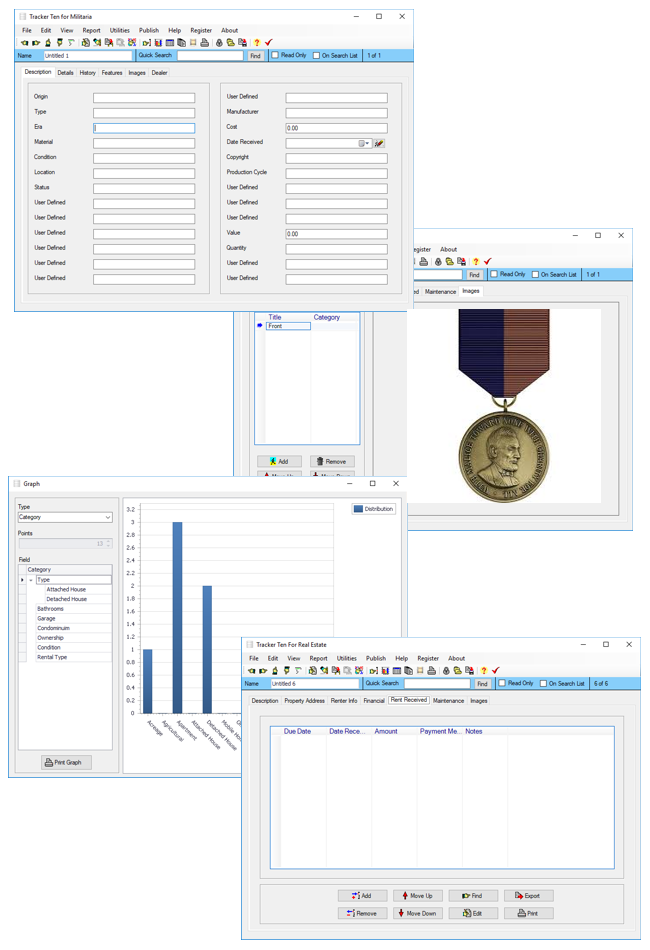

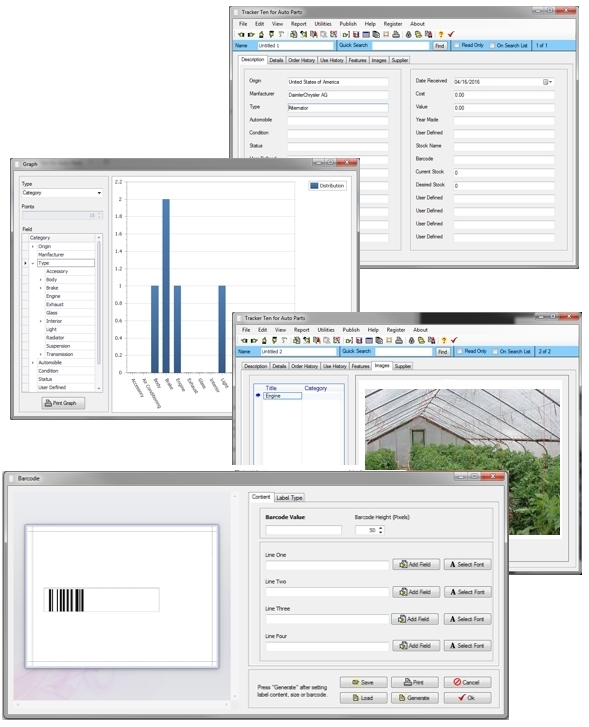

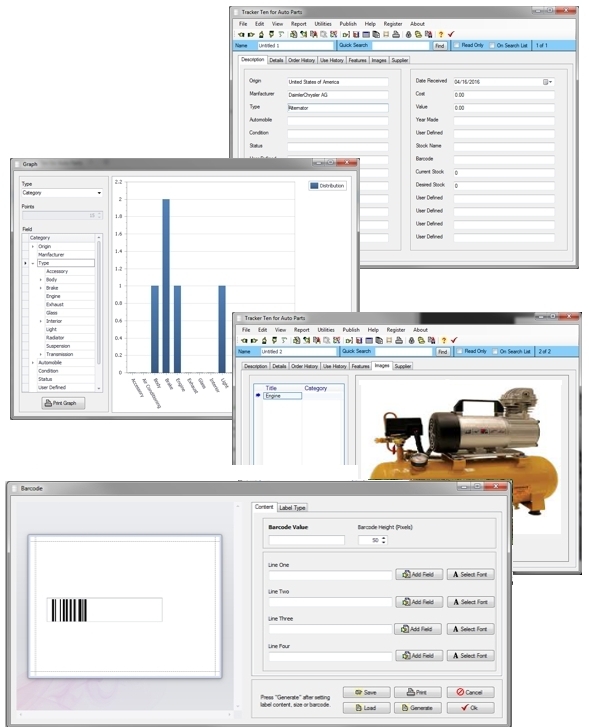

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS All About Barcode Scanners Thursday, September 26, 2024

- NextFiltering Information Wednesday, September 18, 2024