Database

Database Concurrency

Concurrency is one of those database topics that sounds complicated at first, but the idea behind it is actually very simple. At its core, concurrency is about allowing more than one person, process, or program to use the same database at the same time without causing errors, data loss, or confusion. In the modern world, almost every useful database system relies on concurrency. Whether you are checking your bank balance, shopping online, booking a flight, or updating a customer record in a small business application, concurrency is working behind the scenes to keep everything running smoothly.

To understand why concurrency matters, imagine a database as a shared notebook sitting on a desk. If only one person ever writes in the notebook, there are no problems. That person can read, erase, and add notes freely. Now imagine ten people trying to use the same notebook at the same time. One person might be reading a page while another is erasing it. Someone else might be halfway through writing a sentence when another person flips the page. Without rules or coordination, the notebook quickly becomes messy and unreliable. A database without concurrency control faces exactly the same problem.

In database terms, each person or program using the database is called a user or a client, and each set of actions they perform is called a transaction. A transaction might be something simple, like reading a customer name, or something more complex, like transferring money from one account to another. Concurrency is about managing many transactions at the same time in a way that keeps the data correct and consistent.

One of the key goals of concurrency in databases is to make the system fast and efficient. If a database forced users to wait their turn, allowing only one transaction at a time, performance would be terrible. Even a small business system might feel slow, and a large website would become unusable. By allowing transactions to overlap in time, a database can serve many users at once, making better use of computer resources like the CPU, memory, and disk.

At the same time, allowing many transactions to run together introduces risks. The biggest risk is that transactions might interfere with each other. For example, imagine two users updating the same record at the same time. One user changes a price from $10 to $12, while another changes it from $10 to $11. If the database is not careful, one of those updates might be lost, and the final value could be wrong. Concurrency control is the set of rules and techniques that databases use to prevent these kinds of problems.

To better understand concurrency problems, it helps to look at a few common examples. One well-known issue is called a lost update. This happens when two transactions read the same data, make changes, and then write the data back, but one write overwrites the other. The database ends up losing one of the updates, even though both transactions appeared to succeed.

Another common problem is the dirty read. This occurs when one transaction reads data that has been changed by another transaction that has not yet finished. If the second transaction later fails and rolls back its changes, the first transaction has read data that was never really valid. This can lead to incorrect calculations, wrong decisions, or confusing results for users.

There is also the problem of non-repeatable reads. In this case, a transaction reads the same piece of data twice and gets different results each time because another transaction changed the data in between. While this may be acceptable in some situations, in others it can cause serious issues, especially in financial or accounting systems where consistency is critical.

A related issue is known as phantom reads. This happens when a transaction runs the same query twice and sees different sets of rows because another transaction added or removed rows in the meantime. For example, a report might count the number of orders over a certain amount, only to get a different count a moment later, even though the report itself did not change.

To deal with these problems, database systems use transactions with well-defined properties. These properties are often described using the acronym ACID, which stands for Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. Concurrency is most closely related to isolation, but all four properties work together to keep data reliable.

Atomicity means that a transaction is all or nothing. Either all of its changes are applied, or none of them are. This helps prevent partial updates that could leave data in an inconsistent state. Consistency means that a transaction takes the database from one valid state to another, following all the rules and constraints defined in the system. Durability means that once a transaction is committed, its changes will not be lost, even if the system crashes.

Isolation is the property that directly addresses concurrency. It defines how much one transaction can see of another transaction’s work while both are running. Strong isolation makes transactions appear as if they are running one after another, even though they are actually running at the same time. Weaker isolation allows more overlap and better performance, but with a higher risk of concurrency-related issues.

Databases typically offer different isolation levels so that developers and administrators can choose the right balance between performance and correctness. The weakest level allows dirty reads, which can be fast but risky. Higher levels prevent dirty reads, then non-repeatable reads, and finally phantom reads. The strongest isolation level, often called serializable, makes concurrent transactions behave as if they were executed one at a time in some order. This provides the highest level of correctness but can reduce performance under heavy load.

One of the most common techniques used to manage concurrency is locking. When a transaction wants to read or write data, it acquires a lock on that data. A read lock allows other transactions to read the same data but not write it. A write lock prevents other transactions from both reading and writing the data until the lock is released. Locks ensure that only one transaction can make changes at a time, preventing conflicts like lost updates.

While locking is effective, it can also introduce new challenges. If many transactions are competing for the same data, they may spend a lot of time waiting for locks to be released. This can slow down the system and reduce its ability to handle many users at once. In some cases, locks can even lead to deadlocks, where two transactions are each waiting for the other to release a lock, and neither can proceed. Databases have built-in mechanisms to detect and resolve deadlocks, often by canceling one of the transactions.

Another approach to concurrency control is optimistic concurrency. Instead of locking data as it is read, the database allows transactions to proceed freely and checks for conflicts only when they try to commit their changes. If a conflict is detected, one of the transactions is rolled back and may be retried. This approach works well in systems where conflicts are rare, such as applications with many readers and few writers.

Some modern databases use a technique called multi-version concurrency control, or MVCC. With MVCC, the database keeps multiple versions of the same data. When a transaction reads data, it sees a snapshot of the database as it existed at a certain point in time. Writers create new versions of data instead of overwriting existing ones. This allows readers and writers to operate at the same time without blocking each other, improving performance and reducing contention.

MVCC is especially useful in systems with heavy read workloads, such as reporting or analytics. Readers do not need to wait for writers, and writers do not need to wait for readers. The database handles the cleanup of old data versions behind the scenes, ensuring that storage space is used efficiently.

Concurrency is not just a concern for large, high-traffic systems. Even small desktop or single-user databases can run into concurrency issues if they support background tasks, imports, or multiple open windows. As soon as more than one operation can touch the same data at the same time, concurrency becomes relevant. Understanding the basics helps developers design better applications and avoid subtle bugs.

From a practical perspective, good database design can reduce concurrency problems. Keeping transactions short and focused minimizes the time locks are held. Accessing data in a consistent order reduces the risk of deadlocks. Choosing appropriate isolation levels avoids unnecessary overhead while still protecting data integrity. Indexing data properly can also help, as faster queries hold locks for less time.

In everyday use, most people never think about concurrency, and that is a sign that database systems are doing their job well. The complexity is hidden behind simple actions like clicking a button or saving a record. But under the surface, sophisticated concurrency mechanisms are coordinating thousands or even millions of operations, ensuring that data stays accurate and trustworthy.

In summary, concurrency in databases is about safely sharing data among many users and processes at the same time. It balances performance with correctness, allowing systems to be fast without sacrificing reliability. By understanding transactions, common concurrency problems, isolation levels, and control techniques like locking and MVCC, even non-experts can appreciate how much work goes into making databases behave predictably. Concurrency may be invisible to most users, but it is one of the foundations that makes modern digital systems possible.

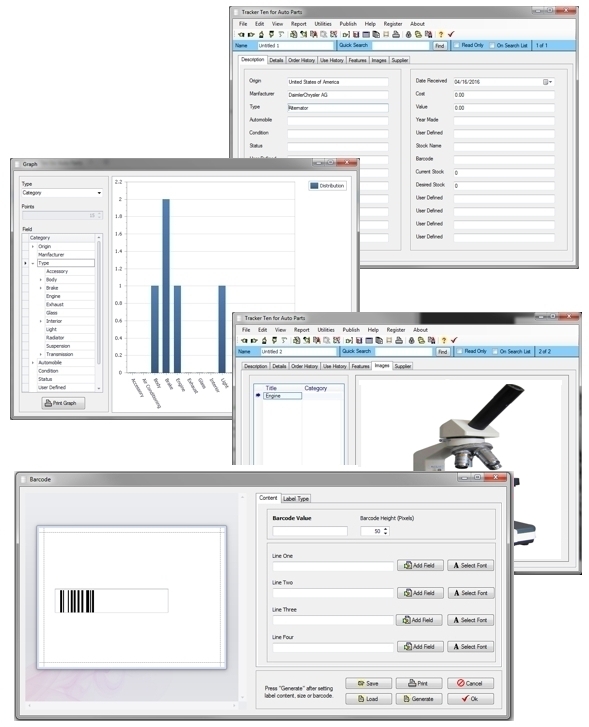

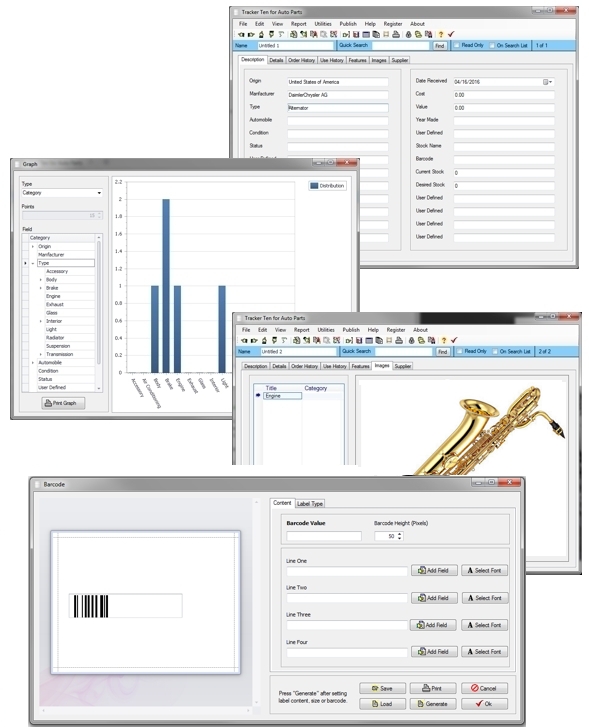

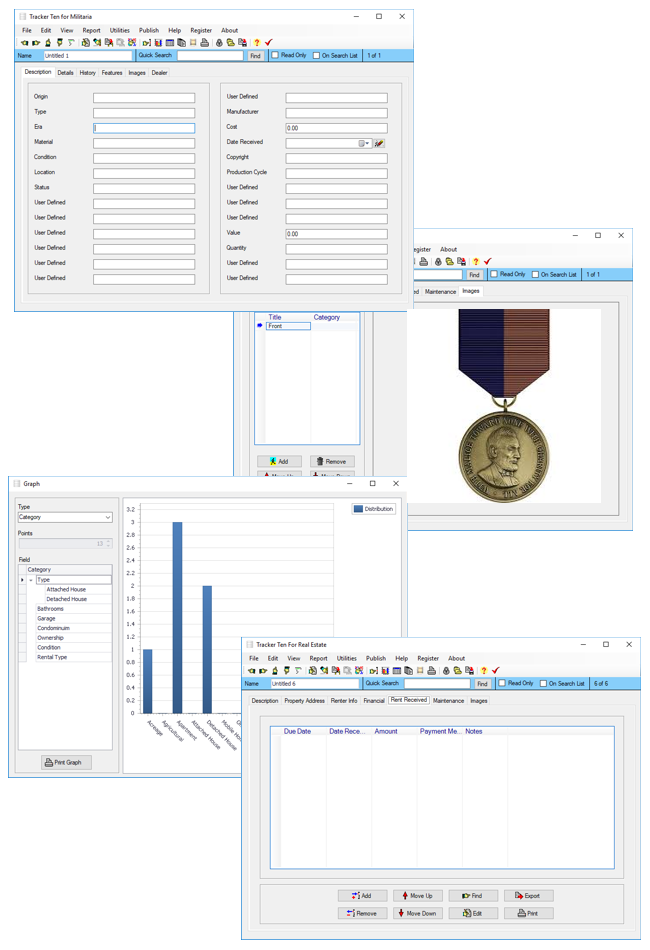

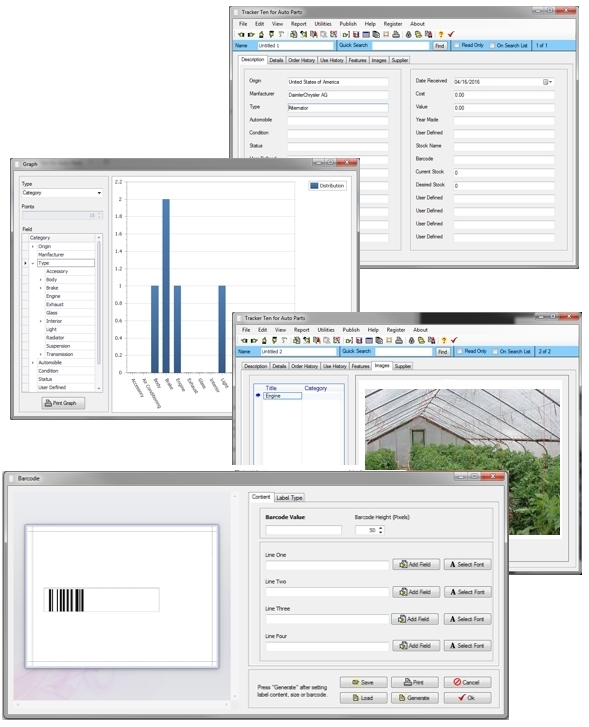

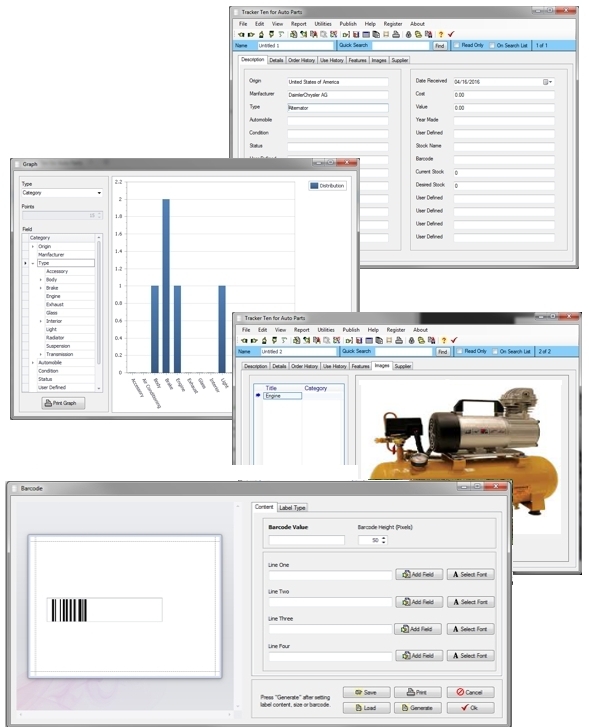

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Inventory Management Best Practices Saturday, May 11, 2024

- NextWhat is a Database Friday, April 26, 2024