Database

Database Normalization

Database normalization is a fundamental concept in relational database design that focuses on organizing data in a structured and logical way to reduce redundancy, minimize dependency, and improve overall data integrity. At its core, normalization is about ensuring that each piece of data is stored in the most appropriate place, only once, and in a form that makes it easy to maintain, query, and update over time.

When databases are not normalized, they often contain duplicate data, inconsistent values, and tightly coupled fields that are difficult to modify without introducing errors. These issues can lead to what are known as data anomalies, including insertion anomalies, update anomalies, and deletion anomalies. Normalization provides a systematic framework for eliminating these problems by decomposing data into well-defined tables based on logical rules.

The goal of normalization is not simply academic correctness, but practical reliability. Well-normalized databases are easier to understand, easier to extend, and far more resilient to change. As applications evolve and data volumes grow, a normalized schema provides a strong foundation that supports long-term scalability and accuracy.

Normalization is most commonly applied in relational database systems such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, MariaDB, SQL Server, and Oracle. However, the principles behind normalization—clear structure, minimized redundancy, and explicit relationships—can also inform the design of non-relational systems and data models used in APIs and data pipelines.

There are several levels of normalization, known as normal forms. Each normal form builds upon the previous one, addressing increasingly subtle forms of redundancy and dependency. While not every database must achieve the highest possible normal form, understanding these levels allows designers to make informed trade-offs based on real-world requirements.

Normal Forms Overview

The concept of normal forms provides a step-by-step methodology for improving database design. Each normal form introduces specific rules that a table must follow in order to qualify. These rules are designed to eliminate particular types of anomalies and structural weaknesses.

-

First Normal Form (1NF): This level requires that each column contains atomic, indivisible values. Tables must not contain repeating groups or multi-valued attributes, and each row must be uniquely identifiable.

-

Second Normal Form (2NF): This level requires that all non-key attributes are fully dependent on the entire primary key. It eliminates partial dependencies that can occur in tables with composite keys.

-

Third Normal Form (3NF): This level requires that non-key attributes are not dependent on other non-key attributes. It eliminates transitive dependencies and further reduces redundancy.

Beyond Third Normal Form, there are additional forms such as Boyce–Codd Normal Form (BCNF), Fourth Normal Form (4NF), and Fifth Normal Form (5NF). These address more advanced dependency scenarios and are typically applied in complex or highly critical systems.

It is important to understand that normalization is not an all-or-nothing process. Many production databases are intentionally normalized only to a certain level, usually 3NF, because higher normal forms can introduce additional complexity without proportional benefit in many real-world scenarios.

First Normal Form (1NF)

First Normal Form establishes the most basic structural rules for a relational table. A table is considered to be in 1NF if it meets the following criteria: each field contains atomic values, there are no repeating groups or arrays, and each record can be uniquely identified.

Atomic values mean that each field holds a single value, not a list or set. For example, storing multiple phone numbers in a single column violates 1NF. Instead, each phone number should be stored in a separate row or a related table.

Repeating groups are another common violation of 1NF. This occurs when a table contains multiple columns that represent the same type of data, such as phone1, phone2, and phone3. While this approach may seem convenient initially, it quickly becomes difficult to manage and query. Normalization replaces repeating groups with related tables that can grow dynamically.

Applying 1NF improves data consistency and simplifies queries. It also lays the groundwork for higher normal forms by ensuring that data is structured in a predictable and uniform way.

Second Normal Form (2NF)

Second Normal Form builds on 1NF by addressing partial dependencies. Partial dependencies occur when a table has a composite primary key and a non-key column depends on only part of that key.

For example, consider a table that stores order details with a composite key consisting of order_id and product_id. If the product_name depends only on product_id and not on the entire composite key, this creates a partial dependency. Such a design violates 2NF.

To bring the table into 2NF, the data must be decomposed into separate tables so that each non-key attribute depends on the full primary key of its table. In this case, product-related information would be moved to a product table, and order-specific information would remain in the order table.

Achieving 2NF reduces redundancy and prevents inconsistencies when updating data. It ensures that each table represents a single concept or entity and that all attributes are directly related to that entity.

Third Normal Form (3NF)

Third Normal Form addresses transitive dependencies, which occur when a non-key attribute depends on another non-key attribute rather than directly on the primary key.

For instance, in a customer table, if the postal_code determines the city and state, and both postal_code and city are stored in the same table, there is a transitive dependency. The city depends on postal_code, not directly on the customer_id.

To achieve 3NF, such dependencies must be removed by creating additional tables. In this example, postal_code, city, and state would be placed in a separate lookup table, and the customer table would reference it.

Third Normal Form is widely regarded as the practical standard for most transactional databases. It strikes a balance between data integrity and usability, ensuring minimal redundancy while keeping schemas understandable and efficient.

Higher Normal Forms

While 3NF is sufficient for most applications, higher normal forms exist to handle more complex dependency scenarios. Boyce–Codd Normal Form refines 3NF by addressing certain edge cases involving overlapping candidate keys.

Fourth Normal Form focuses on multi-valued dependencies, which occur when two or more independent attributes depend on the same key. Fifth Normal Form deals with join dependencies and ensures that tables cannot be decomposed further without losing information.

These higher normal forms are typically applied in specialized domains such as scientific databases, financial systems, or data warehouses where correctness and precision are paramount. In many business applications, the added complexity is not justified.

Benefits of Normalization

One of the primary benefits of normalization is the reduction of data redundancy. Storing data in a single, authoritative location minimizes storage requirements and reduces the risk of inconsistent values appearing in different places.

Normalization also improves data integrity. Because relationships between tables are explicitly defined through keys and constraints, the database can enforce rules that prevent invalid data from being inserted or updated.

Maintenance becomes easier in normalized databases. Updates to a piece of information only need to occur in one place, reducing the likelihood of errors. Queries are often more predictable, and the structure of the data closely reflects the underlying business rules.

From a long-term perspective, normalized schemas are more adaptable. As requirements change, it is easier to add new tables or relationships without disrupting existing data.

Normalization Trade-Offs

Despite its many advantages, normalization is not without trade-offs. Highly normalized schemas often require more joins to retrieve data, which can increase query complexity and, in some cases, reduce performance.

For read-heavy systems or reporting workloads, denormalization may be introduced intentionally to improve performance. This involves duplicating certain data to reduce the need for joins. While denormalization can improve speed, it reintroduces redundancy and must be managed carefully.

The key is balance. Normalization provides a clean, consistent foundation, while selective denormalization can be applied strategically where performance demands it.

Choosing a Normalization Level

The appropriate level of normalization depends on the purpose of the database, the expected workload, and the priorities of the organization. Transactional systems typically benefit from normalization up to 3NF, while analytical systems may use different approaches.

Factors such as query complexity, performance requirements, team expertise, and maintenance costs should all be considered. There is no single correct answer; normalization is a design tool, not a rigid rule.

Normalization in Practice

In practice, normalization begins with identifying entities and their attributes, then determining functional dependencies between those attributes. Designers analyze how data relates and which fields uniquely determine others.

Using these dependencies, data is grouped into tables that minimize redundancy and align with normalization rules. Primary keys, foreign keys, and constraints are defined to enforce relationships and maintain integrity.

This process is iterative. As understanding of the domain improves, schemas may be refined to better reflect real-world relationships.

Database Design Best Practices

Normalization works best when combined with other database design best practices. These include using consistent and meaningful naming conventions, enforcing data validation rules, and creating appropriate indexes to support query performance.

Security considerations such as access control and auditing should be integrated into the design from the start. Scalability should also be considered, ensuring that the database can grow without major structural changes.

Database Schema and Normalization

A database schema defines the structure of the database, including tables, columns, data types, relationships, and constraints. Normalization is the process that shapes this schema into a logical and efficient form.

By applying normalization principles, designers ensure that the schema accurately represents business rules and minimizes the risk of anomalies. Functional dependencies guide how tables are decomposed and related.

A well-normalized schema serves as a durable blueprint that supports both current and future requirements.

Database Normalization Tools

Normalization can be performed manually or with the assistance of specialized tools. Spreadsheets can be used for small datasets, while entity-relationship modeling tools provide visual representations of schemas.

Relational database management systems offer built-in features for defining keys and constraints that support normalization. Dedicated modeling and design tools can further automate analysis and documentation.

The choice of tool depends on the size and complexity of the project, as well as the technical expertise of the team.

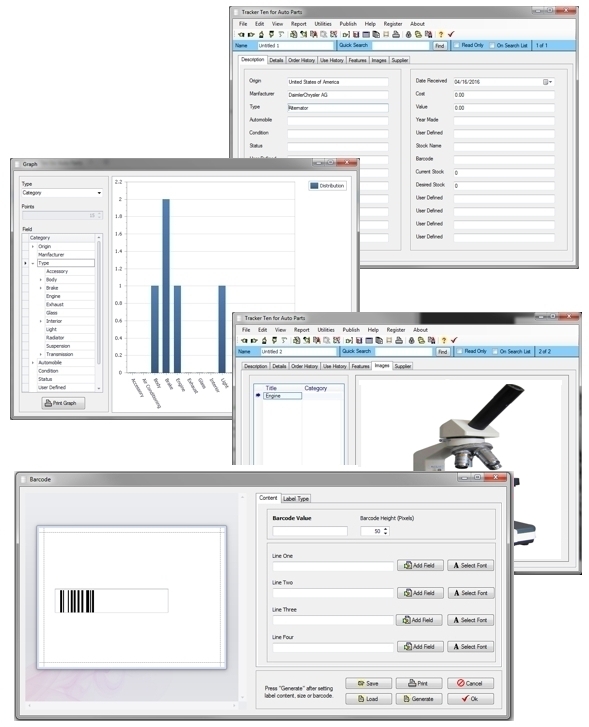

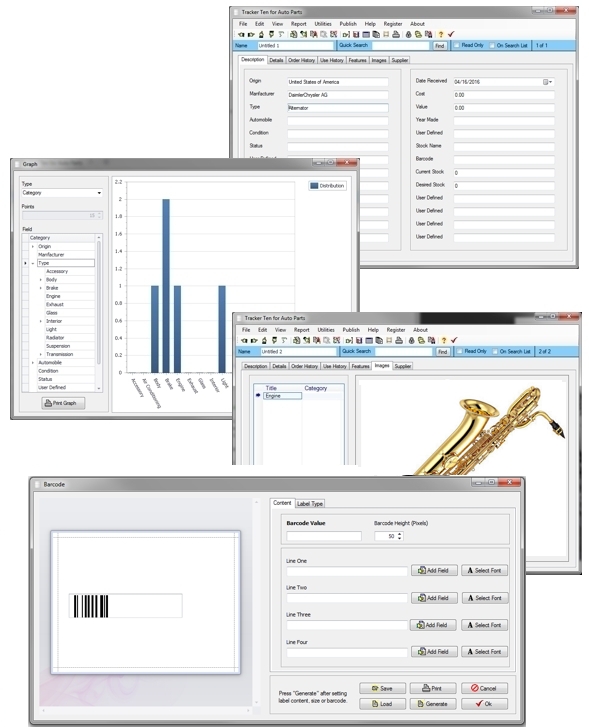

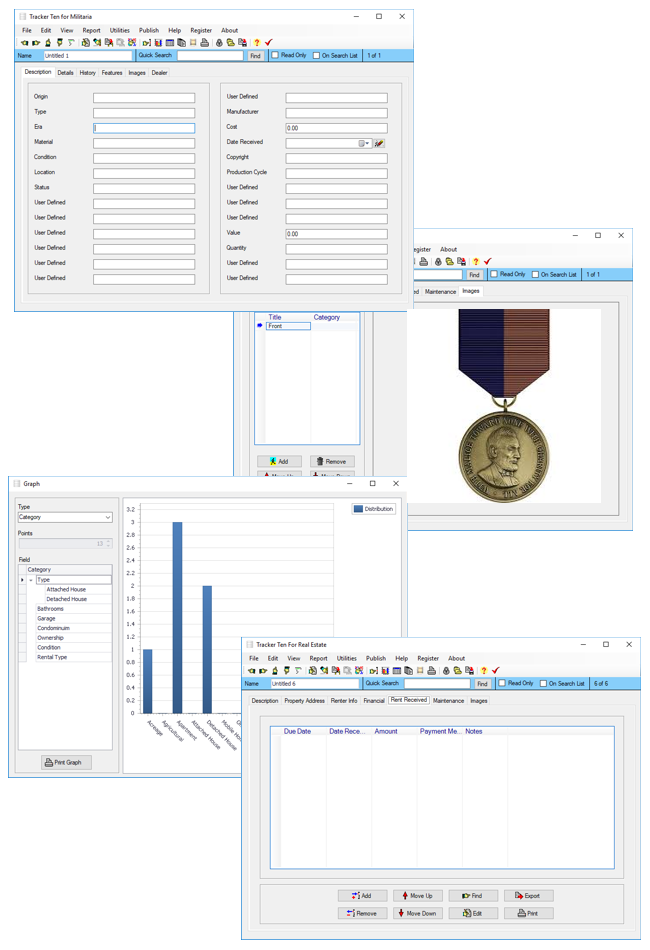

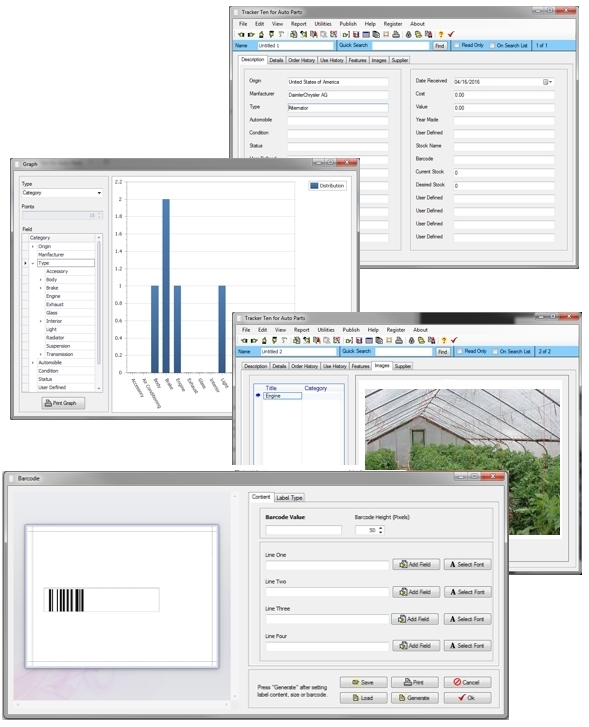

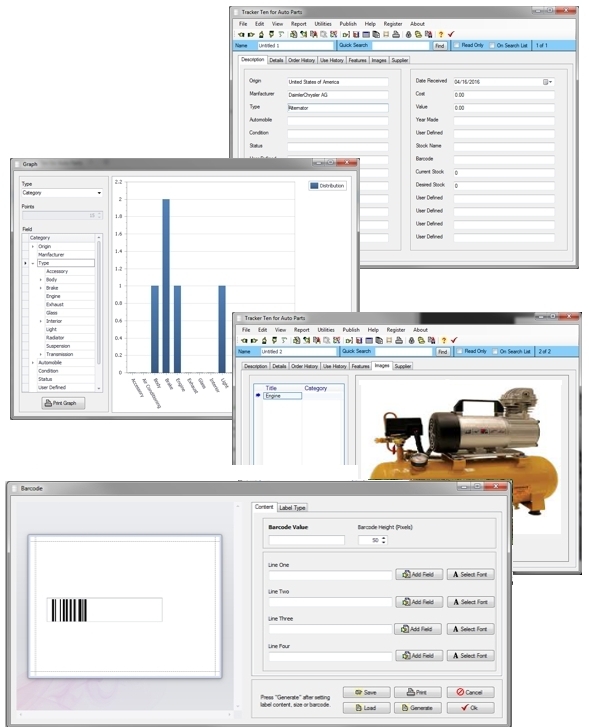

Database Software

Browse our site to explore Tracker Ten, a database software solution that automatically incorporates normalization techniques while maintaining ease of use. By leveraging built-in normalization principles, Tracker Ten helps ensure data consistency, integrity, and long-term reliability without requiring deep database expertise.

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Model Train Collecting Friday, July 28, 2023

- NextFood Database Wednesday, July 12, 2023