Database

What is Metadata

The meaning of metadata is quite simple, yet its implications are extremely broad. Metadata literally means "data about data." It refers to information that describes, explains, categorizes, or contextualizes other data so that it can be more easily understood, found, managed, and used. Metadata can be thought of as a shorthand representation of information that provides insight into the nature, purpose, origin, structure, and usage of a resource, whether that resource is physical or digital.

The primary purpose of metadata is to help people and systems understand and organize data more effectively. By improving clarity and context, metadata enhances data comprehension and utility, making information easier to search, retrieve, analyze, and preserve. Common examples of metadata elements include titles, descriptions, categories, keywords or tags, authors, creation dates, modification dates, file formats, ownership details, and access permissions. When metadata is well designed and consistently applied, it can lead to faster queries and searches, smoother workflows, improved data classification, stronger governance, and more reliable data retention. In short, metadata explains what a resource is, how it should be used, and why it exists.

Metadata is not used only by people. Automated software systems rely heavily on metadata to function efficiently. In large-scale digital environments, metadata is often stored in machine-readable formats such as XML (Extensible Markup Language), JSON, or RDF. These formats allow different systems to interpret and exchange metadata consistently, enabling interoperability between platforms, applications, and organizations.

Although metadata is often discussed in the context of modern computing, it is not a new concept. Metadata has existed for as long as humans have attempted to organize information. Traditional books are a classic example. A book typically contains metadata such as the author’s name, title, publisher, copyright date, edition number, table of contents, page numbers, and an index. None of these elements add new narrative content to the book itself, but they make the information within the book far more usable. Without these metadata elements, finding specific topics or understanding the origin of the content would be far more difficult.

A more modern example of metadata can be found in digital images. Image metadata may include technical attributes such as image dimensions, resolution, pixel density, color depth, camera model, lens type, exposure settings, and file format. It may also include descriptive attributes such as the image title, subject, location, author, copyright holder, and date created. Without this descriptive metadata, managing and searching large image collections would be nearly impossible, especially in professional environments such as journalism, design, digital asset management, and archival preservation.

Whether working with traditional physical objects like books or modern digital assets like images, videos, datasets, or documents, information is only useful if it can be found when it is needed. Metadata provides the structure and context required to make information discoverable. Without metadata, data becomes opaque, disorganized, and difficult to leverage. As data volumes continue to grow exponentially, metadata becomes not just helpful, but essential.

In today’s data-driven world, the explosion of information on the internet, in enterprise systems, and across connected devices has made metadata more important than ever. If you have ever struggled to find relevant information, the problem is often not a lack of data but rather a lack of well-defined, consistent metadata. Content creators, developers, and organizations should therefore pay as much attention to creating high-quality metadata as they do to creating the content itself.

![]()

Types of Metadata

Metadata can be categorized into several different types, each serving a distinct purpose. One common classification includes descriptive metadata, structural metadata, administrative metadata, and operational metadata. While these categories sometimes overlap, they provide a useful framework for understanding how metadata functions in different contexts.

Descriptive metadata is used to describe the content and purpose of a resource. It answers questions such as "What is this?" and "What is it about?" Examples include titles, abstracts, keywords, authors, subjects, and summaries. Descriptive metadata is commonly used in libraries, content management systems, search engines, and digital repositories to support discovery and retrieval.

Structural metadata describes how a resource is organized and how its components relate to one another. For example, in a book, structural metadata defines the relationship between chapters, sections, and pages. In a database, structural metadata defines tables, fields, data types, indexes, and relationships. Structural metadata helps systems understand how data fits together and how it should be processed.

Administrative metadata provides information needed to manage and govern a resource. This includes details about ownership, access rights, usage permissions, retention policies, and compliance requirements. Administrative metadata may also include technical metadata such as file size, format, creation date, and modification history. This type of metadata is critical for data governance, security, and long-term preservation.

Operational metadata focuses on how data is used and processed within systems. It may describe workflows, processing rules, transformation logic, performance metrics, and operational constraints. In data pipelines and enterprise systems, operational metadata helps ensure that data flows correctly and efficiently from one stage to another.

Metadata can range from extremely simple, such as a directory name or file label, to highly complex, such as the schema of a large-scale data warehouse or the metadata model of an enterprise application. Regardless of complexity, the underlying goal remains the same: to make data more understandable, manageable, and useful.

Metadata Storage

Metadata can be stored in different ways depending on the use case and system architecture. In some cases, metadata is embedded directly within the data it describes. In other cases, metadata is stored externally in separate files, databases, or repositories.

An example of embedded metadata can be found in image file formats such as JPEG, TIFF, or PNG. These formats contain not only the raw image data but also embedded metadata fields that describe the image. This metadata may include technical details as well as descriptive information added by the creator or captured automatically by a device such as a digital camera or smartphone.

Metadata can also be stored externally from the data it describes. For example, a document management system may store metadata about files in a database rather than embedding it directly in each file. Similarly, a data catalog may maintain metadata about datasets stored across multiple systems. External metadata storage allows for greater flexibility, centralized management, and easier updates, but it also requires careful synchronization to ensure accuracy.

Metadata in a Relational Database

In relational database systems, metadata refers to the information that defines the structure and behavior of the database itself. This includes tables, columns, data types, constraints, indexes, keys, relationships, views, stored procedures, and triggers. Database metadata describes how data is organized, how it can be accessed, and how different elements relate to one another.

Large-scale database systems such as MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, and Microsoft SQL Server provide built-in mechanisms for accessing metadata. This information is often stored in system catalogs or information schemas, which are read-only views that expose details about all database objects. These metadata views are invaluable for database administrators and developers, as they support performance monitoring, schema analysis, automation, and troubleshooting.

Metadata in relational databases also plays a critical role in application development and integration. Tools that generate reports, build user interfaces, or synchronize data across systems often rely on database metadata to understand the structure of the underlying data. Changes to metadata, such as adding a new column or modifying a data type, can have wide-ranging effects on dependent systems.

Beyond traditional databases, many modern platforms rely heavily on metadata-driven architectures. Customer relationship management systems such as Salesforce use metadata to define layouts, fields, workflows, and business logic. Salesforce even provides a Metadata API that allows developers to retrieve, deploy, and manage metadata programmatically. Similarly, content management systems like SharePoint use metadata to organize and classify documents.

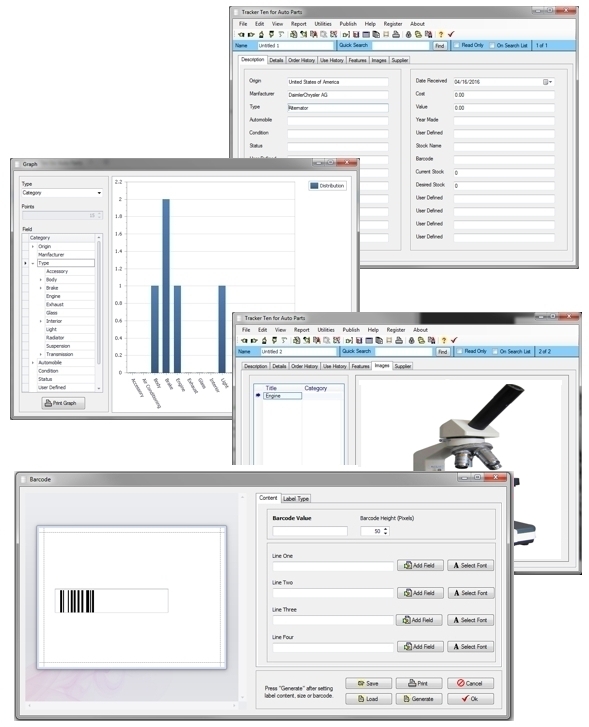

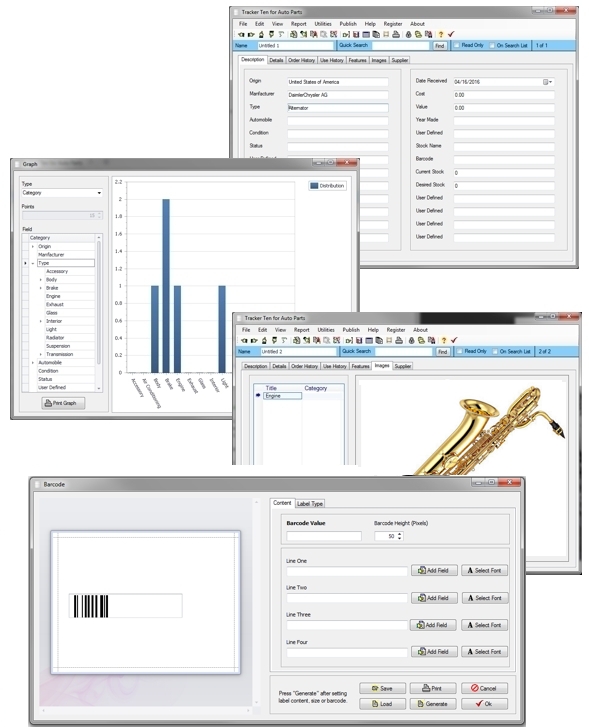

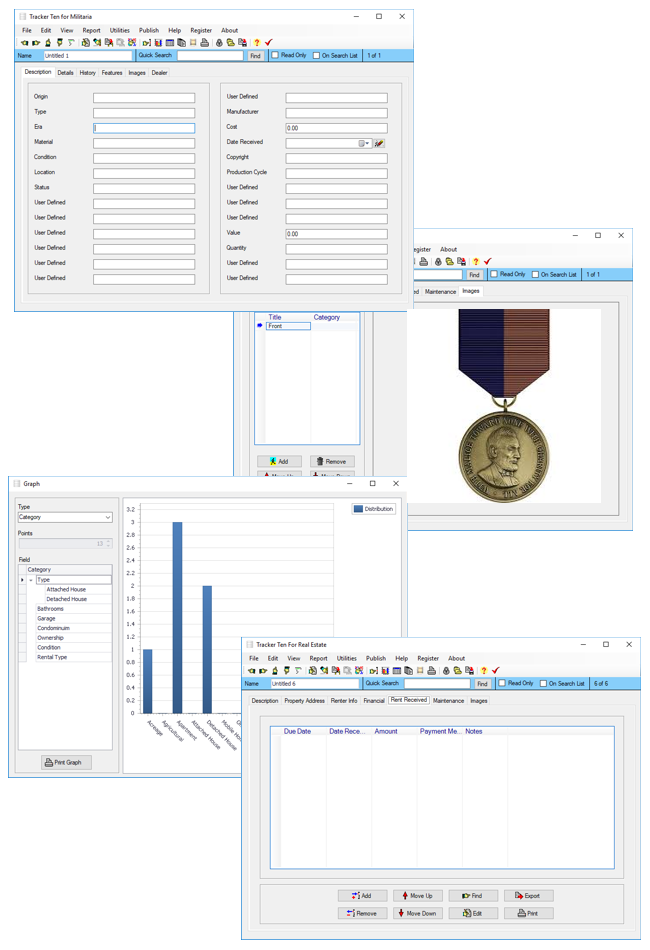

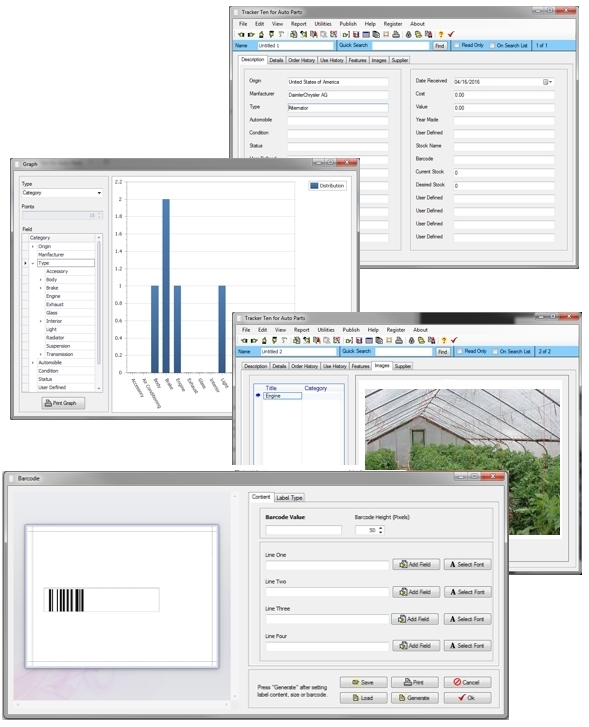

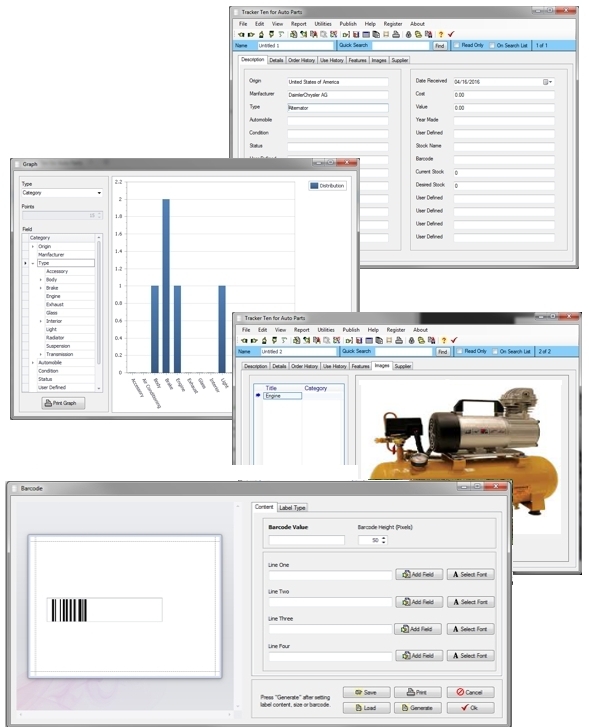

In our own Tracker Ten system, users can define custom metadata for field names, types, and behaviors, allowing the system to adapt to a wide range of use cases without requiring changes to underlying code.

Metadata and Privacy

While metadata provides enormous benefits, it also raises important privacy and ethical concerns. Metadata can be extremely revealing, even when it does not include the actual content of communications or transactions. As a result, metadata can be misused for surveillance, profiling, and tracking.

For example, retail websites may collect metadata about a user’s browsing behavior, purchase history, and interaction patterns. This metadata can be used to infer preferences and send targeted advertisements. Digital marketers may track which websites users visit, how long they stay, and which links they click. Social media platforms rely heavily on metadata to recommend content, connections, and topics of interest.

One of the challenges with metadata and privacy is that the boundary between content and metadata is often blurred. Even if someone has access only to metadata, they can still learn a great deal. For instance, telephone metadata may not include the content of calls, but it typically includes the caller, recipient, location, time, and duration. When analyzed at scale, this information can reveal personal relationships, habits, and routines.

The legal status of metadata under privacy laws varies by jurisdiction and context. In some cases, metadata is treated with the same level of protection as content; in others, it is subject to weaker safeguards. As data collection and analytics capabilities continue to advance, the ethical use of metadata remains an ongoing area of debate and regulation.

Standardization of Metadata

Metadata can be created in many different ways, but inconsistency can significantly reduce its value. To promote interoperability, reliability, and clarity, numerous metadata standards have been developed. These standards define common attributes, vocabularies, and formats that help ensure metadata is interpreted consistently across systems and organizations.

One well-known example is the Dublin Core standard, which provides a simple and widely adopted set of metadata elements for describing digital resources. Another is the Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), which is commonly used in library and archival contexts. More recently, Schema.org has emerged as a dominant standard for structured data on the web.

Schema.org is a collaborative initiative supported by major search engine providers including Google, Microsoft, Yahoo, and Yandex. It provides a shared vocabulary that webmasters can use to mark up content in a machine-readable way. By using Schema.org metadata, websites enable search engines to better understand and index their content, often resulting in richer search results and improved visibility.

Many industries also maintain specialized metadata standards tailored to their specific needs. For example, the Open Geospatial Consortium defines metadata standards for geospatial data, ensuring consistency in mapping and location-based applications. Healthcare, finance, and scientific research all rely on domain-specific metadata standards to support accuracy, compliance, and collaboration.

The lack of metadata standardization can create serious challenges. A frequently cited example is the music industry, where inconsistent metadata makes it difficult to track song ownership and ensure that artists receive proper royalties. When metadata such as artist names, song titles, and contributors is stored in inconsistent formats, automated systems struggle to identify the correct rights holders.

Ultimately, metadata is the foundation of effective information management. As data volumes grow and systems become more interconnected, high-quality, standardized metadata becomes indispensable. By investing in thoughtful metadata design and governance, organizations can unlock the full value of their data while improving discoverability, efficiency, and trust.

Looking for windows database software? Try Tracker Ten

- PREVIOUS Filtering Information Wednesday, September 18, 2024

- NextLivestock Tracking Software Monday, August 26, 2024